Is the 'corporate tax shopping' of global companies over… Now a 'national subsidy' competition [Global Money X-file]

Summary

- The OECD and G20-led global minimum corporate tax introduction has been said to have ended the competition to cut tax rates.

- Global companies are now shifting investment strategies toward countries with strong state subsidies and robust industrial ecosystems.

- South Korea is said to remain competitive amid changes in the global tax environment, with increased inflows of advanced-industry foreign direct investment (FDI).

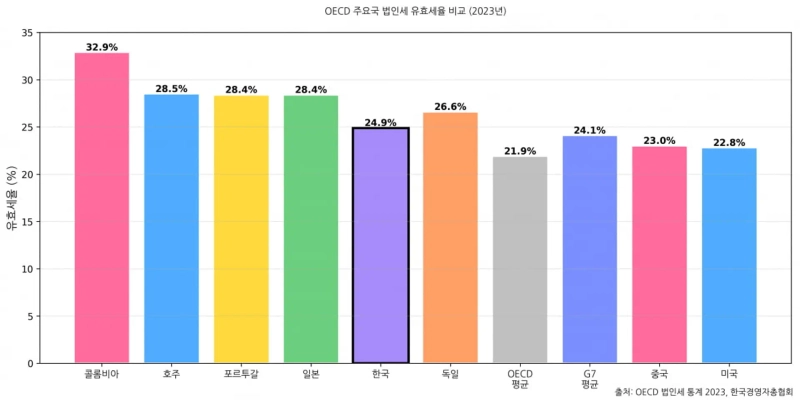

The era of 'tax rate shopping' that global companies have enjoyed for the past 30 years is coming to an end. This is because countries around the world are gradually adopting the 'global minimum corporate tax' led by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Group of Twenty (G20). With a floor set at an effective tax rate of 15%, global companies have no choice but to abandon strategies of moving to places with low taxes. Instead, analyses suggest they are choosing to settle in countries offering strong state subsidies and robust industrial ecosystems.

Is the corporate tax cut competition over?

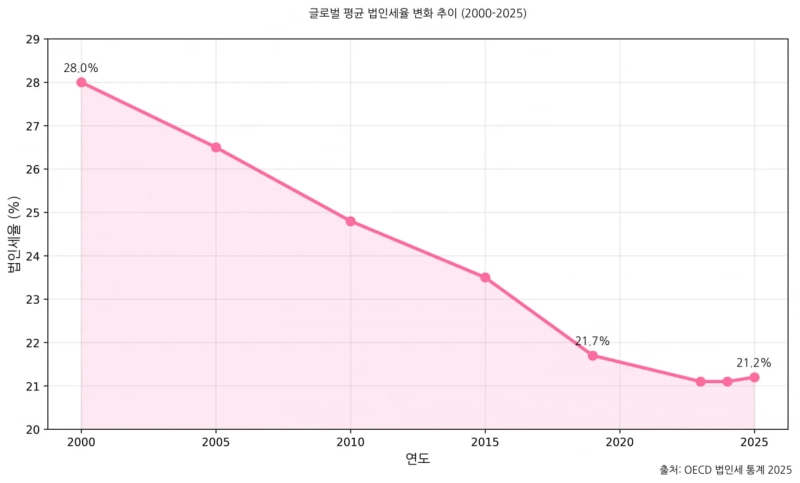

On the 10th, the OECD's "Corporate Tax Statistics 2025" report released last September showed that the global average statutory corporate tax rate this year was 21.2%. The downward trend, which fell sharply from 28.0% in 2000 to 21.7% in 2019, has stopped. It remained at a similar level for the second consecutive year following last year (21.1%).

Analysts say this is because the introduction of the global minimum tax has removed incentives for governments to further lower corporate tax rates. OECD Secretary-General Mathias Cormann emphasized, "The global minimum tax is a powerful tool to prevent tax avoidance," calling it "a historic agreement that puts an end to the race to the bottom on corporate tax rates." He added, "This system is expected to generate about an additional $220 billion in revenue globally each year." That amounts to about 9% of global corporate tax revenues.

The 'tax rate cut competition' among countries to attract companies has diminished. Instead, analyses indicate a fiercer 'subsidy war' has begun. Governments maintain nominal rates while easing corporate burdens through various deductions and cash support.

The EU Tax Observatory said in a related April report that "between 2014 and 2022 the effective tax rate of multinationals in the EU fell from 20.8% to 18.1%, a decline of 2.7 percentage points," and analyzed that "this is the result of a narrowing of the tax base and competition over incentives, not cuts in statutory rates."

In Vietnam you pay taxes and receive 'cash'

Vietnam is a representative case. Foreign companies operating in Vietnam typically enjoyed benefits like "4 years tax exemption, 50% reduction for 9 years," resulting in low effective tax rates in the 5–10% range. But the situation changed when Vietnam introduced the 'Qualified Domestic Minimum Top-up Tax (QDMTT),' one of the global minimum tax measures, from 2024. Global companies operating in Vietnam must pay to the Vietnamese government the amount of tax falling short of 15%.

Instead, to prevent the departure of global companies, the Vietnamese government established an "Investment Support Fund" financed by the additional tax revenues collected. The government plans to return the taxes paid by companies in the form of cash subsidies. Under the OECD model rules, 'cash subsidies' are treated not as tax reductions but as corporate 'income.'

The United States' Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) produces a similar effect. The U.S. offers the 'Advanced Manufacturing Production Tax Credit (AMPC)' for batteries produced by foreign companies building battery plants in the United States. Under OECD rules, ordinary tax credits lower the effective tax rate and trigger additional top-up tax liabilities.

However, the U.S. designed the AMPC as a so-called 'transferable tax credit.' In that case, the benefit is regarded not as a tax reduction but as an 'asset' or 'income' that the company can sell on the market. In other words, the denominator (income) increases while the numerator (tax) remains, so the drop in the effective tax rate may be minimal. From the perspective of foreign companies investing in the U.S., there are cases where they can receive substantial subsidies in the U.S. without needing to pay additional tax in their home countries.

Global investment flows also change

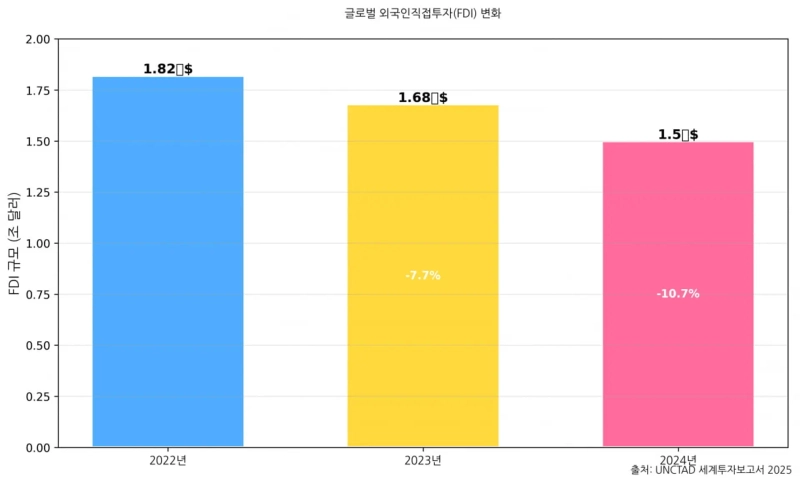

Recent changes in the global tax environment have also altered global capital flows. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) "World Investment Report 2025," global foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2024 amounted to $1.5 trillion, an 11% decrease from the previous year. High interest rates, geopolitical uncertainty, and a reduction in tax incentives dampened investment sentiment. In particular, FDI flows to Europe plunged by 58%.

On the other hand, some analyses say South Korea has been relatively unaffected by this trend. South Korea's reported FDI in 2024 was $34.5 billion, a 5.7% increase from the previous year, marking a record high for the second consecutive year. In particular, manufacturing FDI inflows surged to $14.5 billion, up 21.6% from the previous year. Semiconductors, bio, and other advanced industries led the upswing. This indicates that global companies' and investors' interest is shifting to places with established industrial ecosystems such as semiconductors and batteries.

There are variables. The Trump administration in the United States has adopted a so-called 'Side-by-side' approach that partially exempts or relaxes the application of the minimum tax to its domestic companies.

The U.S. decided to fully exclude the application of the OECD global minimum tax's IIR (Income Inclusion Rule) and UTPR (Undertaxed Profits Rule) to groups that include a U.S. parent company.

Instead, it has demanded that the international community accept a U.S.-style global minimum tax. The G7 also said it supports 'side-by-side' solutions in this direction. Concerns have arisen that this could create a tilted playing field, favoring U.S. companies. However, nothing has been finalized yet.

For South Korea, the introduction of the minimum tax is a 'double-edged sword.' In the short term, it can assert taxing rights over low-tax profits of overseas subsidiaries. It could increase tax revenues by collecting additional corporate tax from foreign companies in Korea.

But in the long term, critics argue it could prompt global companies to 'leave Korea.' There are calls for South Korea to urgently transition to measures such as infrastructure support for power, water, and labor, and to 'refundable tax credits.'

Reporter Kim Ju-wan kjwan@hankyung.com

Korea Economic Daily

hankyung@bloomingbit.ioThe Korea Economic Daily Global is a digital media where latest news on Korean companies, industries, and financial markets.

!['Easy money is over' as Trump pick triggers turmoil…Bitcoin tumbles too [Bin Nansa’s Wall Street, No Gaps]](https://media.bloomingbit.io/PROD/news/c5552397-3200-4794-a27b-2fabde64d4e2.webp?w=250)

![[Market] Bitcoin falls below $82,000...$320 million liquidated over the past hour](https://media.bloomingbit.io/PROD/news/93660260-0bc7-402a-bf2a-b4a42b9388aa.webp?w=250)