Exchange rate unfazed even by US intervention… Is there another ‘wild card’? [Bin Nansa’s Wall Street Without Gaps]

공유하기

Summary

- It reported that growing co-movement between yen weakness and won weakness is heightening concerns over the USD/KRW rate and an expansion of risk-asset volatility.

- It said that pressure from the US Treasury secretary and the Bank of Japan for rate hikes, and whether the yen turns stronger, could become a turning point for Asian currencies and global risk-asset capital flows going forward.

- It reported that if the BOJ shifts to a more hawkish monetary policy than expected, it is necessary to keep in mind the potential for an expansion of short-term market volatility—including yen carry-trade unwinding, a yen spike, and profit-taking in the small- and mid-cap rally.

Bessent’s unusual verbal intervention as US Treasury secretary

Brakes on the won and yen, vying for the weakest exchange-rate performance

Warning to Japan: “Sound monetary policy needed”

Yen nearing its lowest level in 40 years

Growing co-movement with the won’s weakness

US presses the Bank of Japan to raise rates

If the yen suddenly swings sharply stronger

USD/KRW could drive volatility in risk assets as well

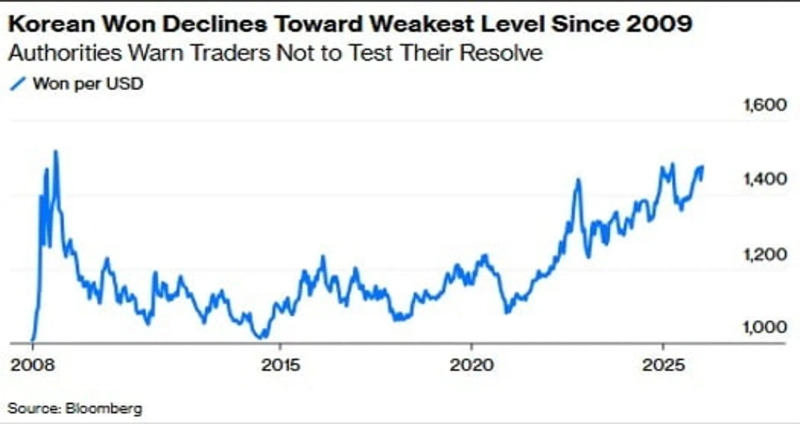

The exchange rate’s rise shows little sign of stopping. Despite various controversies, the government has been mobilizing every tool at its disposal, yet the won–dollar rate has been unable to retreat from its highest level since 2009. Typically, a country’s currency value is said to reflect the strength of its economy and its future growth outlook. The won’s current decline is troubling not only because of immediate side effects such as higher import prices and fears of capital outflows, but above all because the belief that “the won could fall further” can trigger additional won selling and further exchange-rate increases—creating a self-fulfilling vicious cycle.

Looking back, the times when the exchange rate surged to anything like today’s level were the declaration of martial law, the global financial crisis, and the foreign exchange crisis. Setting aside political interpretations, there are also points that do not line up with those past episodes when you look only at economic indicators such as a narrowing rate differential with the US, a record-high current account surplus, and a decline in credit default swap (CDS) premiums that signal sovereign credit risk. This suggests that part of the current exchange-rate spike appears to involve factors that are difficult to explain with purely domestic issues alone. Of course, the bigger reasons may include factors absent in the past—a $350 billion investment plan in the US, a worsening aging trend, concerns over declining potential growth, and rising demand for dollar holdings among corporates and individuals.

Against this backdrop, on the 14th (local time), US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent made an unusual intervention-like remark (a verbal intervention) to curb the USD/KRW rise. Right after meeting Deputy Prime Minister Koo Yun-cheol, he issued a statement saying, “Excessive volatility in the FX market is undesirable,” and “The recent won weakness is inconsistent with Korea’s solid economic fundamentals.” Although the move largely faded within two days, the exchange rate—above 1,478 won ahead of the meeting—plunged at one point to 1,462 won in a single move.

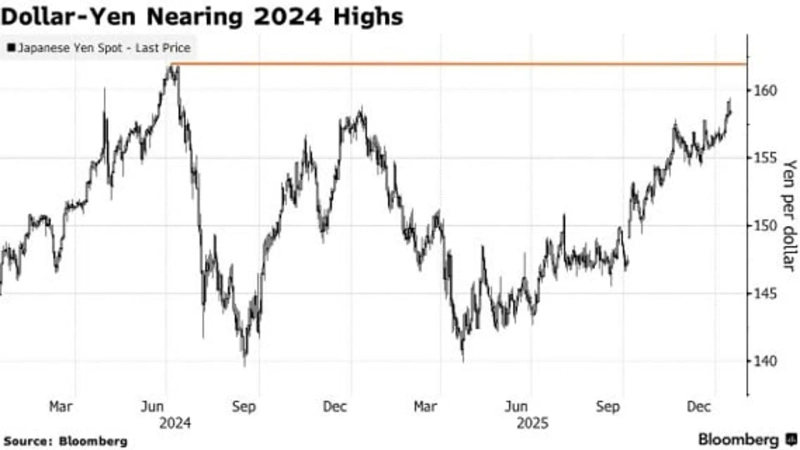

However, Secretary Bessent’s verbal intervention was aimed not only at the won but also at the Japanese yen. That is because USD/JPY has also been approaching its highest level since 2024. Notably, 2024 was when USD/JPY hit its highest level in roughly 40 years. At the time, the Japanese government carried out actual market interventions multiple times to defend the currency, and the Bank of Japan hinted at faster-than-expected rate hikes, sending the yen sharply higher and jolting global financial markets. It was an episode in which yen carry-trade funds—borrowing cheap yen to invest in risk assets worldwide—were unwound in an instant.

ADVERTISEMENT

That said, Bessent’s remarks on the won and the yen differed slightly in tone. After meeting Japan’s Finance Minister Katayama on the 13th, he likewise warned speculative players betting on yen weakness, saying “excessive FX volatility is inherently undesirable.” But he also added that he “emphasized (to the Japanese side) the need to formulate and communicate sound monetary policy.” In effect, he reiterated the view that the Bank of Japan needs to raise rates to fundamentally address the extreme yen weakness. Since last year, Bessent has consistently pointed out that “the BOJ’s pace of rate hikes is too slow.”

Why is the US making an unusual currency intervention?

Why would the US Treasury secretary step in to rein in currency weakness in Korea and Japan? In Korea’s case, the intent is clear. Having secured a pledge of $350 billion in direct investment from Korea, an overly weak won is unfavorable for executing those investments.

The two countries previously agreed that when Korea deploys an investment fund in the US capped at $20 billion per year, it “should not cause instability in the FX market.” Bank of Korea Governor Rhee Chang-yong also noted, “If the FX market remains as unstable as it is now, it will be difficult to set up the annual $20 billion fund,” adding, “Under the MOU as well, if exchange-rate volatility is high, it could be agreed that we may not proceed with establishing the fund.”

ADVERTISEMENT

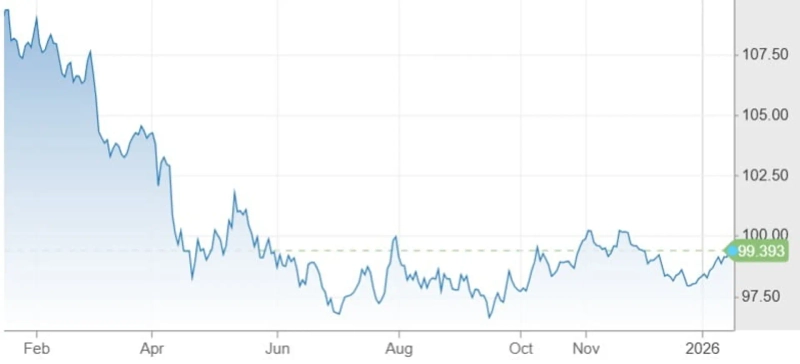

Then why the pressure on the Japanese yen? Because the ‘moderate dollar weakness’ sought by the Trump administration is not materializing, amid far more severe weakness in Asian currencies led by the yen. The core economic strategy of the Trump administration is to reduce the trade deficit and boost manufacturing investment in the US through tariffs, a weaker dollar, and low interest rates. As a result, after the launch of Trump’s second term, the ICE Dollar Index—which had been close to 110—fell at one point to the 96 level.

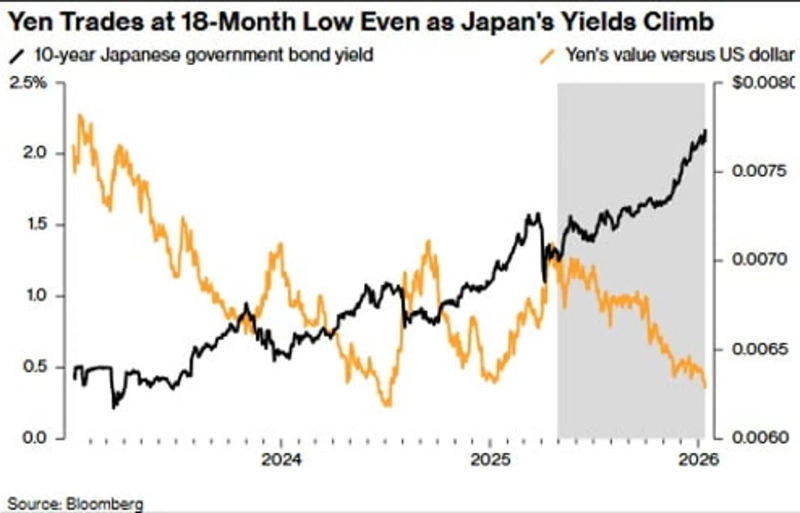

But the dollar index has climbed back to around 99 since last November. Optimism about the US economy and early-year geopolitical tensions are fueling dollar strength. The yen—supposed to share a safe-haven role—has lately slid to an 18-month low despite various geopolitical risks, preventing the dollar’s relative strength from being contained. The yen has the second-largest weight in the currency basket that determines the ICE Dollar Index.

Moreover, a sharp drop in Japanese government bond prices (= higher yields) is also pushing up long-term US Treasury yields. This is an obstacle to President Trump’s plan for low interest rates.

This simultaneous decline in Japan’s currency and bond values is, of course, influenced by Sanaenomics (the economic stimulus policy of Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi). Expectations that large-scale fiscal expansion led by Prime Minister Takaichi and a stance of restraining BOJ rate hikes could gain more traction after an early general election have recently deepened yen weakness and lifted long-term Japanese yields. Ultimately, the view that excessive yen weakness is hindering the economic environment sought by the Trump administration is what led to Bessent’s verbal intervention—and to a call for “sound monetary policy (effectively, rate hikes)” that was not made of Korea.

The yen’s shadow behind the won’s slide

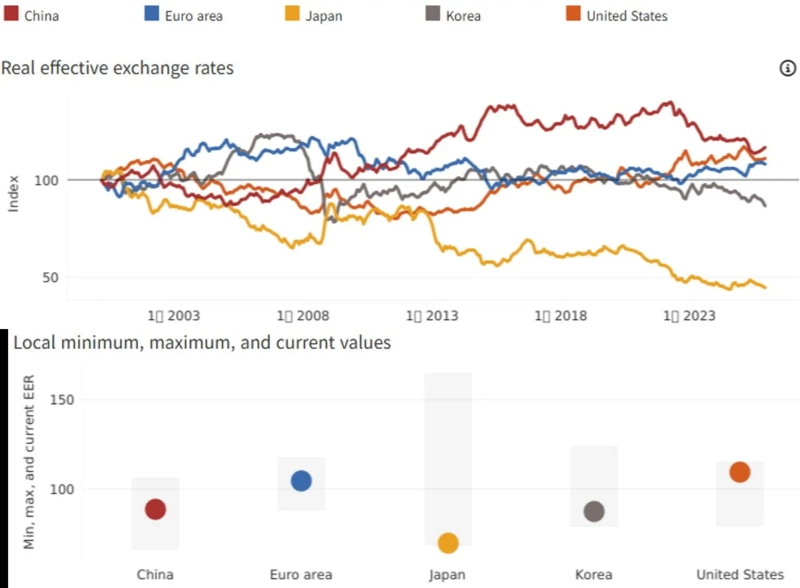

Looking at the real effective exchange rates compiled monthly by the BIS (Bank for International Settlements) for 64 countries, as of last November the Japanese yen ranked 63rd and the won 60th. The won’s slide is shocking, but the yen was worse.

When this yen weakness finally comes under control could also become a turning point for Korea’s exchange rate, because the co-movement between the won and the yen has been strengthening. A regression analysis of weekly exchange-rate fluctuations over the past five years found that when the yen weakens by an average of 1% against the dollar, the won weakens by 0.46%. But over the past three months, that co-movement has been even stronger. While the yen weakened about 4.9% versus the dollar, the won fell about 3.4% versus the dollar—and 90% (3.1 percentage points) of that decline occurred alongside the yen.

This does not mean the won’s weakness was caused by the yen’s weakness (a causal relationship), but that the correlation was strong. The Bank of Korea likewise analyzed that, of January’s exchange-rate rise, factors specific to won weakness accounted for 25%, while the remaining 75% reflected yen weakness, dollar strength, and geopolitical risks.

“The cautious BOJ could change”

As the yen approaches the psychological resistance level of 160 per dollar, the Japanese government has also been raising the intensity of verbal intervention day after day to defend the currency. 160 yen is also the line at which Japan has carried out actual market interventions in the past. Voices on Wall Street warning about the possibility of real intervention and the ensuing fallout are steadily growing.

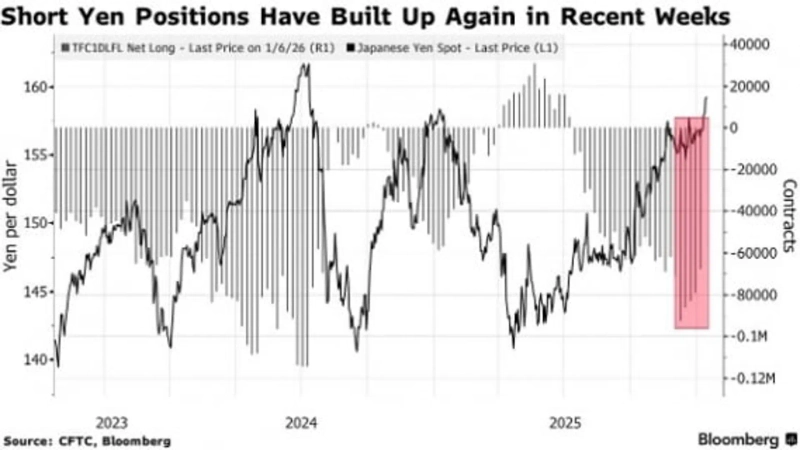

But the effect has been minimal. While the market views the 160–165 yen range as an “intervention-risk zone,” it continues to bet on yen weakness. According to Nomura International’s London FX options trading desk, in large options trades of $100 million or more, call options betting that USD/JPY will rise to 165 yen (= yen depreciation) outnumber put options by more than two to one.

This is because the prevailing view is that even if real intervention by Japanese authorities temporarily pushes USD/JPY lower, a trend reversal is unlikely. Shibata, chief strategist at Tokai Tokyo Intelligence Lab, said that a significant share of current options orders to buy dollars and sell yen are clustered in the 162-yen range; if 162 yen breaks, USD/JPY could quickly surge to 170 yen. He also assessed that “if real interest rates remain in negative territory, a structural shift to yen strength will not be easy.”

In the end, it means that fundamentally preventing excessive yen weakness requires BOJ rate hikes. Accordingly, BOJ Governor Kazuo Ueda has recently continued to signal the need for rate increases. Goldman Sachs projected that “the BOJ is moving away from its previously cautious stance,” and could raise the pace of hikes from once a year to twice a year (semiannually). It also said, “the next hike will likely be in July, but if the yen declines further, the timing could be brought forward.”

Yen carry risk—even if not as large as before

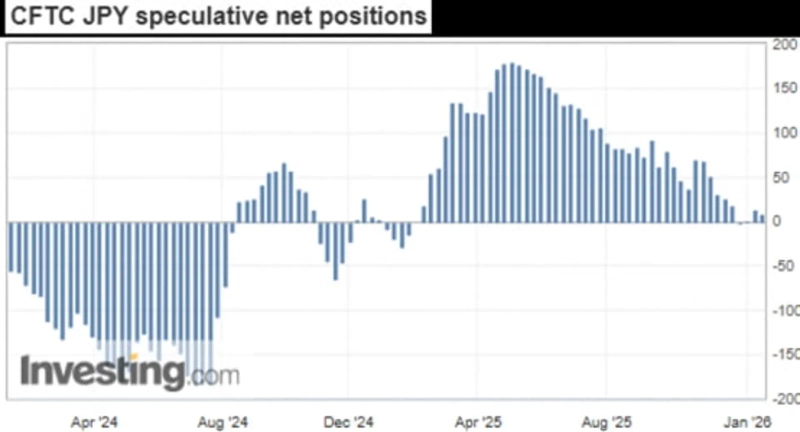

If the BOJ truly raises rates faster than the market expects or sends a hawkish signal, concerns are emerging that the yen carry-trade unwinding that battered global equity markets in August 2024 could be repeated.

The BOJ will announce the results of its monetary policy meeting on the 23rd. A hold is seen as certain this time, but if it reveals a more hawkish tilt than the market expects, that alone could lead to yen appreciation and instability in risk assets. In particular, it could provide a catalyst for profit-taking in the small- and mid-cap rally that was hot at the start of the year.

Of course, many counter that the spillover from a yen carry unwind will not be as large as in 2024. Hedge funds hold net short yen positions, but across speculative funds as a whole, net yen positioning is around neutral. In other words, the risk that excessive short positioning triggers a short squeeze → sharp yen surge → yen carry unwinding is not large. Japanese authorities are also steadily ratcheting up the intensity of verbal intervention, conditioning the market.

Still, the fact that even the US Treasury secretary is stepping in to manage the yen exchange rate suggests that Asian currency weakness has reached a tipping point. A shift to yen strength is an important inflection point for the won’s exchange rate as well, but above all it could shake up capital flows concentrated across risk assets.

After the rally supported by early-year equity optimism and the January effect, the market is increasingly shifting into a structure that reacts more sensitively to downside factors. Investors, too, need to keep in mind that the BOJ could pivot to a more hawkish stance faster than expected—and that significant short-term volatility could arise in the process—when considering risk management.

New York=Correspondent Bin Nansa binthere@hankyung.com