$3 trillion ‘shadow banking’ put to the test…Private credit ‘maturity bomb’ looms [Global Money X-File]

공유하기

Summary

- It said refinancing burdens have increased as private credit originated in 2021 enters a wave of maturities and refinancing cycles starting in the first half of this year.

- It reported that amid persistently high rates, signs of stress include 20% and 50% mark-to-market losses on senior loans held by private credit funds, along with an increase in PIK options and NAV loans.

- It said the FSB, JPMorgan and others warned of a lack of transparency in non-bank finance and the potential for liquidity spillovers through bank-linked credit lines.

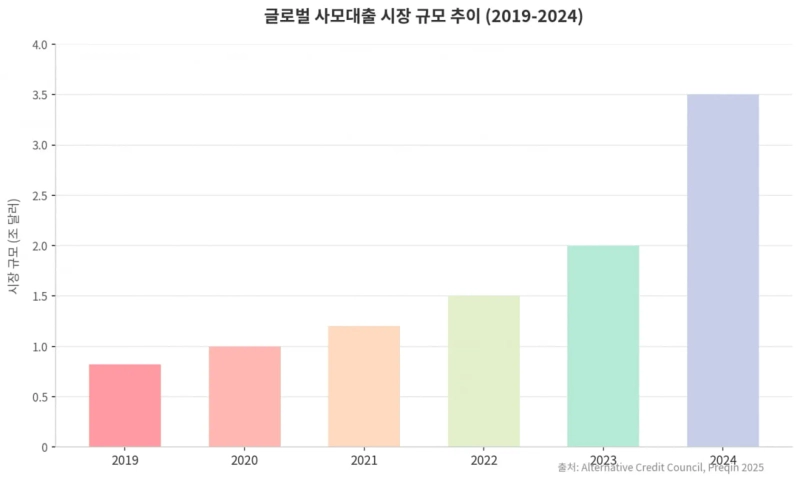

Private credit coming due in large volumes this year has emerged as a potential flashpoint for global financial markets. Analysts say the $3 trillion shadow-banking system is being put to the test over whether it can function properly in a ‘new normal’ of high rates and low growth.

A wave of maturities this year

According to the U.S. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) on the 21st, the average maturity of private credit loans was tallied at about 5.4 years (median 5.25 years). That is shorter than the typical seven-year maturity of bank-syndicated leveraged loans (BSL). In other words, massive volumes of loans originated in 2021 are set to enter their maturity and refinancing cycle starting in the first half of this year.

Earlier, the flood of liquidity unleashed to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic flowed into the less regulated private credit market rather than banks. In 2021, many market participants deployed capital aggressively on the expectation that rates would remain low. Companies at the time were granted lofty valuations—15 times EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization), even 20 times. They were able to raise hundreds of billions of dollars at low interest rates in the 4–6% range.

But today’s macro environment is different from 2021. Even with the U.S. central bank (Fed) pivot, the all-in rate—SOFR (Secured Overnight Financing Rate), the benchmark for private credit, plus a credit spread—exceeds 8–11% for mid-sized companies.

Hamilton Lane, a U.S. private investment manager, said in its 2025 private credit report that the annual interest cost on loans financed in 2021 at a benchmark rate (SOFR, etc.) plus 5 percentage points was about 6%. It analyzed that, as rates rose, the rate on loans with the same structure had climbed to about 9.3% by March 2025.

Howard Marks, co-founder of Oaktree Capital Management, noted that the ‘easy money’ environment created by abnormally low rates from 2009 to 2021 has ended, and that it is unlikely the next few years will see a return to ultra-low rates like those of the past.

Signs of stress emerging

A refinancing crunch does not simply mean corporate bankruptcies. Unlike banks, the private credit market operates a mechanism that does not visibly disclose distress externally, allowing problems to fester internally. Related signals fall into three broad categories. First is a decline in collateral value. For refinancing to proceed smoothly, the value of the borrower company—used as collateral—must be maintained.

However, according to Reuters, an MSCI (Morgan Stanley Capital International) analytical report released in January found that, among senior loans held by private credit funds, the share of assets posting mark-to-market losses of more than 20% versus par has surged more than threefold since 2022. More troubling, the proportion of assets suffering losses of around 50%—effectively wiping out half the principal—has exceeded 5% of the total.

Zombie companies are also rising quickly. When borrowers lack the cash to pay interest, managers often propose a ‘PIK (Payment-in-Kind)’ option rather than immediately declaring a default. This structure capitalizes interest by adding it to the loan principal instead of paying in cash. According to Lincoln International, the share of deals including a PIK option was only about 7% in Q4 2021, but rose to 10.6% in Q3 2025, showing a clear uptrend.

Brian Garfield, global head of portfolio valuation at Lincoln International, said, “Of the recent surge in PIK, 57% is ‘Bad PIK’—not in the original contract but added after the fact as the borrower’s situation deteriorated,” adding that “this is the clearest evidence that cracks have emerged in the private market.”

This means a widespread form of ‘life support’—rolling debt with more debt—at companies that cannot even cover interest with the money they earn. When interest is added to principal, compounding causes total debt to grow exponentially. If a loan with a 12% annual rate is converted entirely to PIK, the principal owed doubles in six years.

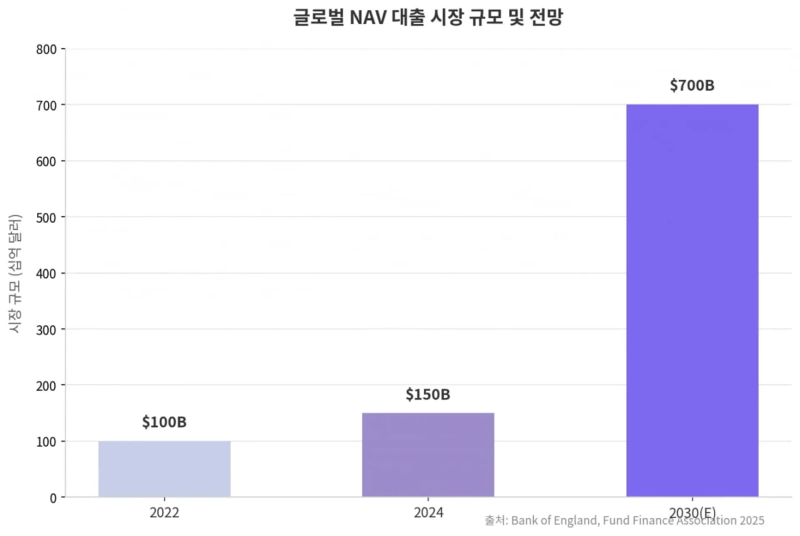

The last-resort tool managers turn to when refinancing is blocked is so-called ‘NAV (net asset value) lending.’ It is a financial technique that raises another loan secured not by an individual company but by the fund’s overall assets. According to UK private credit investment manager 17Capital, the global NAV lending market is projected to grow to $700 billion by 2030 (about KRW 945 trillion).

Critics say this is a dangerous gamble that piles leverage on top of leverage. NAV loans have repayment priority, pushing existing limited partners (LPs), such as pension funds, structurally down the waterfall. If a fund breaks down, LPs face a higher risk of being left with nothing.

‘Not a systemic crisis’ vs. ‘invisible risks’

Some argue the concerns are overblown. Stephen Schwarzman, chairman of Blackstone, the world’s largest private equity manager, said in a recent interview that “concerns about private credit are exaggerated.” There is also a view that Blackstone’s portfolio has an average loan-to-value (LTV) ratio in the 40% range, more conservative than banks.

Bank of America also projected that the private credit default rate would edge down this year to 4.5% from about 5% in 2025. Optimists argue that, as the impact of rate cuts filters through with a lag, companies will get some breathing room. Torsten Slok, chief economist at Apollo Global Management, said that “rates will remain high, but as the odds of a soft landing for the U.S. economy increase, borrowers’ repayment capacity will improve.”

Counterarguments are just as forceful. Jamie Dimon, chairman of JPMorgan Chase, recently said, “The private credit market has never really gone through a recession,” warning of systemic risk: “If you find one cockroach here, it’s just the beginning of thousands hiding.”

This crisis is not a ‘bank run’ like the 2008 financial crisis, where deposit withdrawals rush bank counters. Instead, it can take the form of a so-called ‘silent credit crunch,’ in which corporate funding lines dry up without noise.

Private credit is not priced daily on an exchange. ‘Fair values’ calculated by managers’ internal models do not immediately reflect market shocks. This delays loss recognition by several quarters, even years, when a crisis hits. The Financial Stability Board (FSB) warned in a report late last year that “non-bank financial assets total $256.8 trillion, accounting for 51% of the overall financial system, but the private credit segment lacks transparency due to severe data limitations.”

Private credit—often called ‘shadow banking’—is not an isolated island disconnected from banks. According to analyses by the Fed and BofA, among others, the amount of credit facilities (revolvers) and lending provided by U.S. banks to private credit funds or BDCs (business development companies) totals about $300 billion (about KRW 420 trillion). If private credit funds are hit by a liquidity crunch and draw down their bank-established ‘credit lines’ en masse—akin to overdrafts—banks’ liquidity could be depleted in an instant.

In fact, the bankruptcy of auto parts maker First Brands last October highlighted the market’s vulnerabilities. As news of the bankruptcy broke alongside allegations of accounting fraud, a ‘flash crash’ hit the U.S. loan fund and ETF market, with about $1.5 billion flowing out in a single month.

Risks in the global private credit market also affect Korea’s financial system. That is because the period when Korea’s major institutional investors—National Pension Service, Korea Investment Corporation, and various mutual aid associations—most aggressively increased overseas alternative investments was precisely the problematic window ‘around 2021.’

By Kim Ju-wan, kjwan@hankyung.com