'$8.9 trillion bomb'… Emerging-market debt flips the switch on the economy [Global Money X-File]

Summary

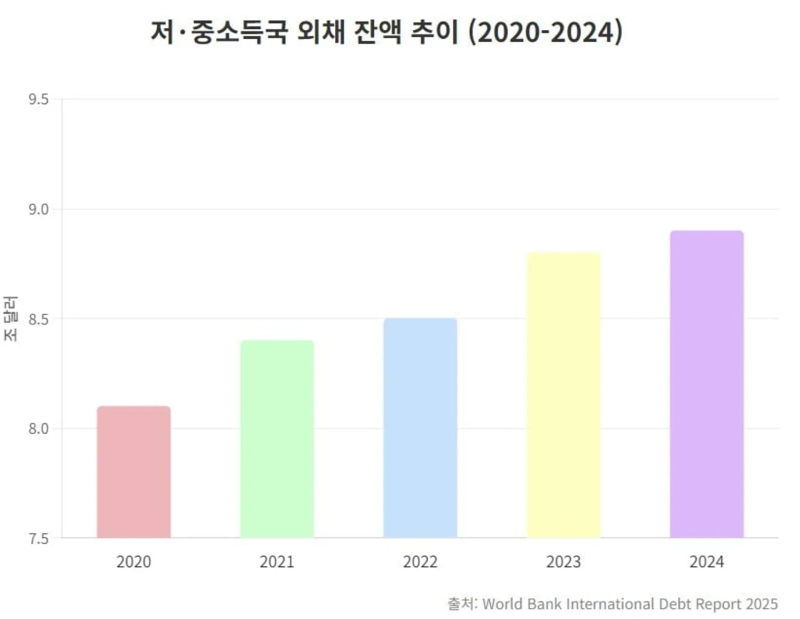

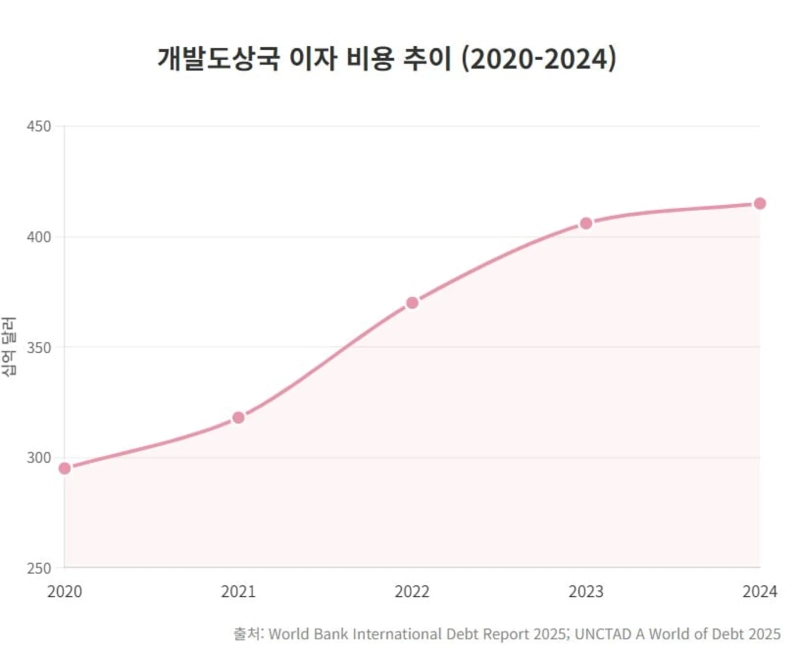

- It said government debt in low- and middle-income countries—along with external debt outstanding of $8.9 trillion and interest costs of $415 billion—has reached record highs, becoming a flashpoint for the global economy.

- It reported that repayment pressure is sharply cutting public infrastructure investment and imports, weakening global aggregate demand and trade and undermining future growth engines.

- It said the IMF and the World Bank warned that low growth, high debt, delayed debt restructuring, and domestic-debt risks are squeezing emerging-market investment, potentially disrupting the export front line for export-dependent economies including South Korea.

Concerns are mounting that rising government debt in low- and middle-income countries could become a flashpoint for the global economy. The worry is that it is eroding the world economy’s underlying fundamentals. Some analysts also warn it will dampen demand in the global real economy.

Record-high repayments

According to the World Bank’s “International Debt Report 2025,” released last month, over the three years from 2022 to 2024 developing countries repaid $741 billion more in principal and interest to external creditors than they borrowed in new funds. It marked the largest net capital outflow recorded in the 50 years since the World Bank began compiling relevant statistics in the 1970s.

Put simply, it means poorer countries are not borrowing to finance growth; instead, they are tightening their belts—cutting school budgets to free up funds—and funneling the proceeds to Wall Street asset managers, London hedge funds, and the vaults of Beijing’s policy banks. The “trickle-down effect of capital” has vanished, and a “reverse transfer of wealth,” in which money is sucked from poorer places to richer ones, has become entrenched.

Typically, capital flows from advanced economies (capital-abundant countries) with lower returns to developing economies (capital-scarce countries) with higher growth potential. Advanced economies earn interest income, while developing countries grow through investment—a “win-win” structure. But that mechanism has recently broken down.

The principal and interest repayments by developing countries are not merely a transfer of funds. They can also imply a structural decline in global aggregate demand. As funds from developing countries—where the propensity to consume is high—move to financial institutions in advanced economies—where the propensity to consume is low—they may reduce real consumption and investment worldwide.

Indermit Gill, the World Bank’s chief economist, said, “Even if global financial conditions appear to be improving, developing countries must not fool themselves,” adding that “they are not out of danger yet.”

He continued, “Debt accumulation is continuing, sometimes in new and more toxic ways,” and added that “policymakers should use this ‘breathing space’ to restore fiscal soundness, rather than rushing back to markets to borrow again.”

As of end-2024, external debt outstanding in low- and middle-income countries swelled to a record $8.9 trillion. The interest costs these countries paid in 2024 alone hit a record $415 billion, a sharp increase from the previous year.

Real economy slips into stagnation

A debt crisis hits the real economy—on the ground in infrastructure and manufacturing. As debt rises, the first budget item governments tend to cut is often public infrastructure investment deemed “not immediately urgent.” Investment momentum has cooled across 56 “frontier market” countries often touted as next-generation growth engines.

According to the World Bank, in the 2020s the average annual growth rate of per-capita investment in these countries has fallen to around 2%. That is less than half the 2010s average (in the 4% range). When investment stalls, it means future growth engines are also being lost.

Many countries under repayment pressure pursue so-called “import compression” policies to prevent foreign-currency outflows—blocking imports of machinery, electronics, and intermediate goods except for essential food or energy. According to IMF research, in the aftermath of a default, imports in the affected country fall by an average of 15%, directly translating into weaker exports for trading partners.

Bolivia last year is a case in point. After foreign-exchange reserves ran dry and it became unable to pay for fuel imports, the Bolivian government tightened controls on private-sector dollar conversion and blocked import settlements.

As a result, Bolivia’s imports plunged, and neighboring countries and global companies that exported manufactured goods to Bolivia took a hit to sales. UNCTAD (the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) reported that “3.3 billion people live in countries that spend more on debt interest payments than on education or health.”

The international community has for years called for swift and efficient debt restructuring. But conditions have instead worsened. Some experts diagnose this as a “structural bottleneck” born of the complexity of the modern financial system.

The biggest obstacle is “hidden collateral.” Resource-rich countries such as the Republic of the Congo and Malawi borrowed in the low-rate era by pledging proceeds from oil or mineral sales as collateral. In an October policy paper last year, the IMF noted that “collateralized borrowing is a key factor that makes restructuring difficult.”

In the 1980s–90s, debt crises could be resolved by negotiating with a small number of Western commercial banks or advanced-economy governments. Today, the creditor landscape is complex and fragmented. The share of emerging donor countries such as China, India, and Saudi Arabia has surged. Eurobond creditor groups—made up of thousands of anonymous private investors—are also entangled.

“Non-bond commercial loans,” unlike Eurobonds, often lack collective action clauses (CACs). CACs are provisions that compel minority creditors to follow an agreement once a majority of creditors consent.

Without them, loan contracts are vulnerable to holdout behavior, where even a small number of dissenters can block an overall restructuring. The IMF estimates the average time from a default declaration to restructuring has lengthened from 1.1 years in the past to 2.5 years recently.

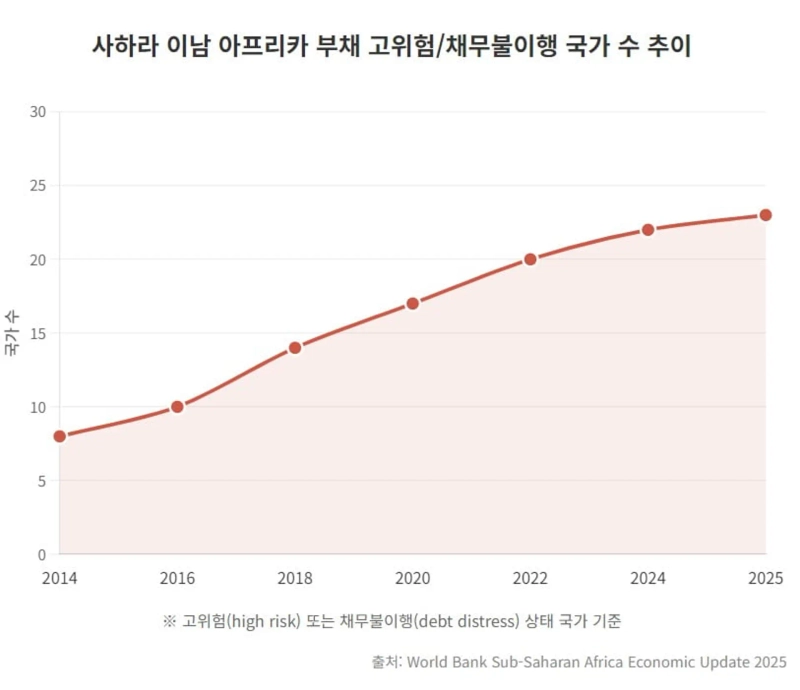

The most lethal flashpoint in the global debt crisis is “domestic debt.” According to the IMF, among low-income countries, the share of countries where domestic public debt accounts for more than half of total public debt doubled from the 10% range in 2014 to 21% in 2024. The problem is that domestic commercial banks hold these government bonds as assets.

If the government writes down debt, the domestic banking system’s assets can deteriorate, making bank runs more likely. In Ghana’s case, the process of carrying out a domestic debt exchange ahead of external debt restructuring delivered a massive shock to the financial sector. Cut external debt and overseas credibility suffers; cut domestic debt and domestic banks fail—this intractable dilemma, analysts say, is blocking a swift resolution.

Kristalina Georgieva, Managing Director of the IMF, said at last year’s G20 finance ministers’ meeting that “the global economy is trapped in a ‘low growth, high debt’ cycle,” adding that “in particular, debt-servicing costs in emerging markets are squeezing investment, and this is a major driver of worsening global inequality.”

For South Korea’s highly trade-dependent economy, a developing-country debt crisis is not a distant problem. Its fallout can already show up on the ground in exports and orders. Korea’s exports to emerging markets make up a substantial share of the total. But as purchasing power in these countries weakens amid a debt crisis, the export front line is disrupted. Even if headline growth holds up on the back of a semiconductor boom, export channels for traditional manufacturing are narrowing.

Reporter Kim Joo-wan kjwan@hankyung.com

Korea Economic Daily

hankyung@bloomingbit.ioThe Korea Economic Daily Global is a digital media where latest news on Korean companies, industries, and financial markets.