Fund 'giants' that shake companies while managing assets as large as a trillion-dollar GDP... In Korea too? [Global Money X-file]

Summary

- The rapid growth of the global ETF market has strengthened the voting power and control of a few large asset managers such as BlackRock, the article reported.

- It stated that this common ownership phenomenon could weaken market competition and potentially lead to price increases and reduced innovation.

- In the Korean market, the National Pension Service was described as acting as an overwhelming 'common owner' in key domestic industries due to its massive assets and influence.

As ETF investing becomes the 'trend'

Passive managers like BlackRock

grow in 'size' exponentially

Absolute influence over companies

In Korea, the National Pension Service 'dominates'

![Fund 'giants' that shake companies while managing assets as large as a trillion-dollar GDP... In Korea too? [Global Money X-file]](https://media.bloomingbit.io/PROD/news/ac11d381-c370-47ee-a1d0-d1931006d48b.webp?w=800)

"Passive investing," considered one of the most successful investment approaches in 21st-century financial markets, is being criticized for potentially unsettling the competitive principles that underpin capitalism. The rational strategy of low-cost, broadly diversified investment across the market has rapidly spread as the choice of millions of investors. However, a few large asset managers have accumulated massive funds and increased market dominance, and analysts say their decisions now effectively steer global capital flows and corporate structures.

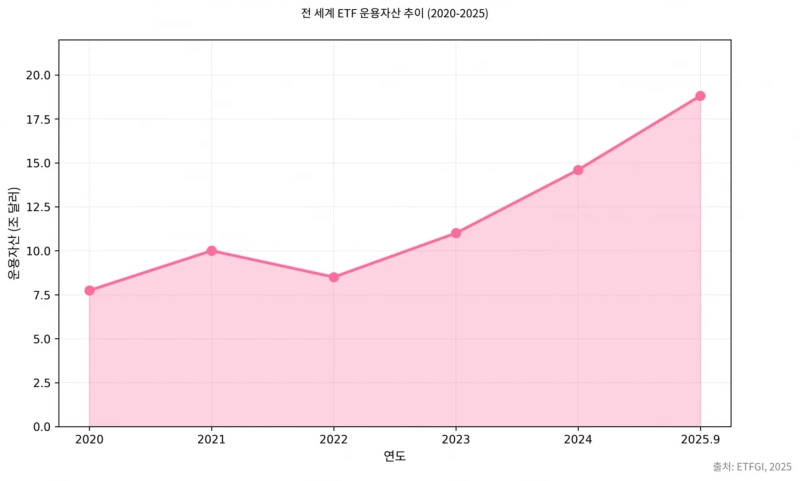

ETF assets under management surpass $18 trillion

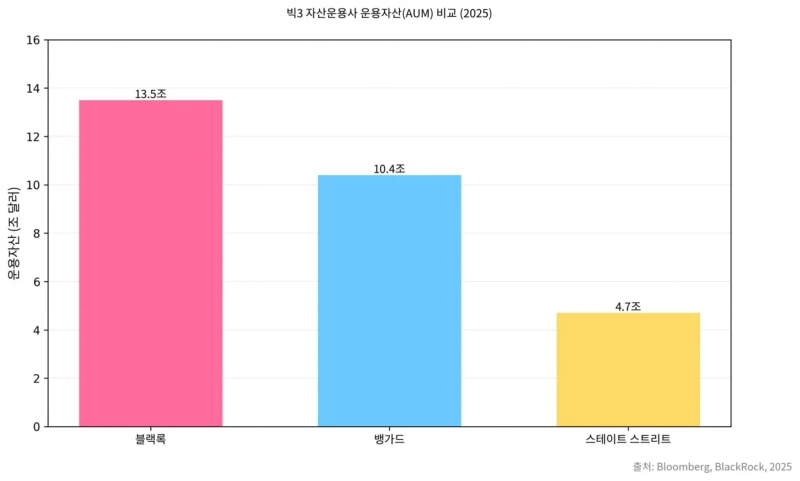

According to ETFGI, a specialist research firm for the global ETF and ETP industry, as of September global ETF assets under management reached $18.81 trillion, an all-time high. The assets under management (AUM) of giant global asset managers also grew. As of the third quarter this year, BlackRock's total AUM reached an all-time high of $13.5 trillion. Adding Vanguard (about $10.4 trillion) and State Street (about $4.7 trillion) brings the combined assets managed by these three firms to well over $28 trillion, roughly comparable to a national GDP of the trillion-dollar country.

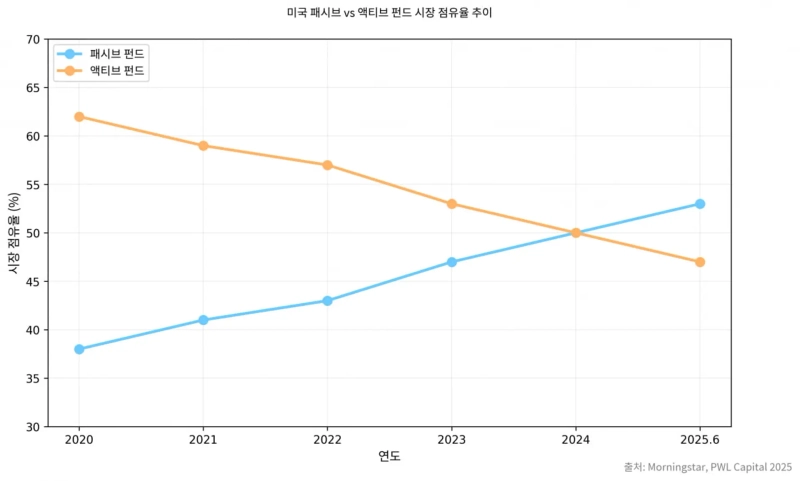

The past 20 years are seen as a period in which passive investing overwhelmed active investing and seized market hegemony. It became known that the long-term efforts of active fund managers to outperform market-average returns often failed to overcome high fees. Index funds and ETFs became the standard for savvy investors. In the U.S. market, passive funds had a market share of 53% as of 2024, surpassing active funds (47%).

The rise in the influence of the 'big three' asset managers is not simply due to their strategic offensives. Analysts say it is the result of the structural characteristics of passive (non-active) investment products combined with the principle of market efficiency. The asset management industry is fundamentally dominated by economies of scale. As assets under management grow, per-unit costs of running funds fall rapidly. For this reason, the early leaders that expanded their size and lowered fees naturally came to dominate the market.

A representative example is Vanguard. The firm cut fees on as many as 87 funds even in February 2025. Reuters estimated that the annual cost savings for investors from this could be about $350 million. Such 'fee-cutting competition' is not mere marketing; it has become a key factor reshaping competition across the industry.

Only a few huge managers able to maintain a low-cost structure based on massive assets survived this fight, and as a result their market dominance solidified. The rise of the 'big three' is not accidental but a structural outcome of economies of scale and market efficiency.

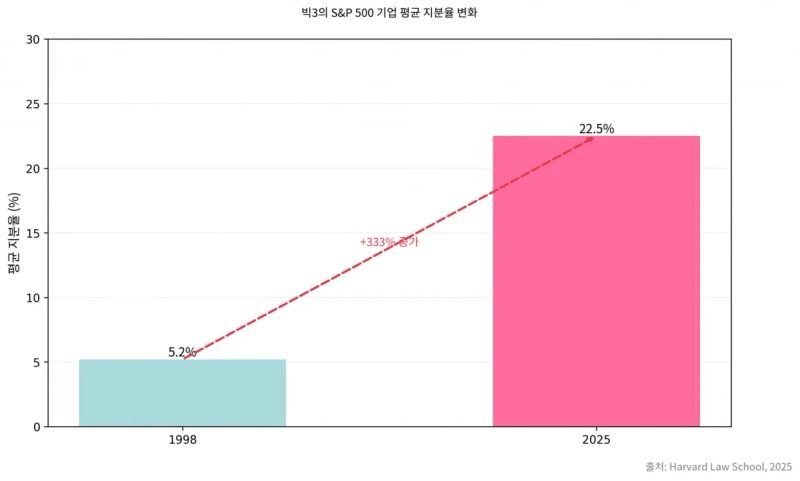

Concentration of funds in passive vehicles has changed ownership structures in U.S. industry. As of last month, the 'big three' are estimated to hold an average combined stake of about 20% to 25% in S&P 500 companies. Compared with 5.2% in 1998, this represents an increase of more than fourfold in roughly two decades.

More important than stake percentages is the practical voting influence. Institutional investors have higher shareholder meeting participation rates than individual investors. According to research by Lucian Bebchuk of Harvard Law School and Scott Hirst of Boston University, as of 2021 the median share of voting power the 'big three' exercised in director elections at S&P 500 companies was about 27.5% (BlackRock 9.8%, Vanguard 12.0%, SSGA 5.7%).

Lucian Bebchuk, a Harvard Law School professor, wrote in the paper "The Power of the Big Three, and Why It Matters," "We live in an unprecedented era in the history of corporate governance," adding, "A small number of index fund managers exercise enormous voting power across almost all major publicly traded firms." He emphasized, "Their power comes not only from what they do, but also from what they decide not to do."

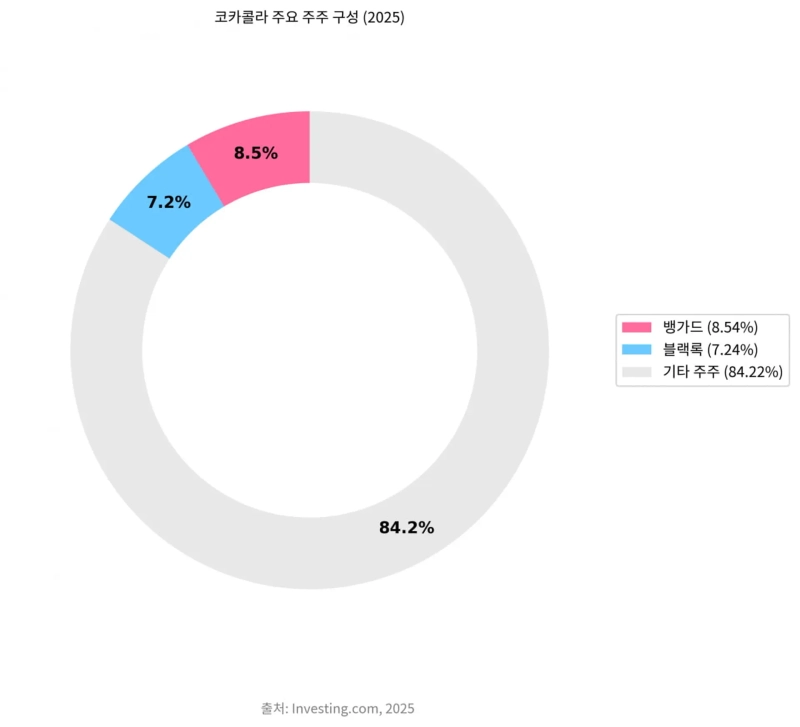

This ownership structure has oddly reshaped industrial landscapes. According to Investing.com, as of 2025 Coca-Cola's major institutional shareholders include Vanguard (about 8.54%) and BlackRock (about 7.24%). Rival PepsiCo's largest shareholders also include Vanguard (about 10.01%) and BlackRock (about 8.49%).

In the airline industry, Vanguard is the largest shareholder of both Delta Air Lines (about 11.5%) and United Airlines (about 11.53%). This means fiercely competing firms effectively share the interests of the same major owners.

Loss of competitive incentives and price increase controversy

The core of the 'common ownership' problem lies in what shareholders — the owners of companies — aim to achieve. Traditional shareholders were straightforward. They wanted the specific company they invested in to outperform competitors and generate more profit. Winning in competition and expanding market share directly translated into their returns.

But the emergence of 'common owners' (co-investors) changes that simple objective structure. For example, if an investor holds stakes in both airline A and airline B, it may make little difference to them whether A beats B or B beats A. In fact, if the two companies ease competition, raise prices, and share profits, the investor's overall portfolio value may rise.

Traditional shareholders aim to maximize a single firm's profits, while common owners aim to maximize the total profits across all firms they hold. Economists note that this difference can weaken market competition and create structures unfavorable to consumers. The issue raises a fundamental question about how far the competitive principles of capitalism should be permitted to operate.

For example, if Vanguard holds stakes in both Delta and United, Delta cutting prices to take customers from United is effectively moving money from one pocket to another for Vanguard. Price competition that reduces industry-wide profitability could lower the total portfolio value.

Therefore, common owners theoretically have incentives to prefer stable total industry profits over aggressive market-share competition by individual firms. Critics argue this can send implicit signals to corporate managers to reduce competition, cut investment, and slow the pace of innovation.

Martin Schmalz, a finance professor at the Saïd Business School, University of Oxford, noted, "Firms compete only when they have the incentive to compete," adding, "Common ownership reduces these incentives." He further said, "From the investor portfolio perspective, market share is a zero-sum game. Attempts to win share by cutting prices simply reduce total industry profits."

The U.S. airline industry shows how this theoretical possibility can play out in reality. In 2018 Jose Azar, Martin Schmalz, and Isabel Tecu analyzed U.S. domestic route data from 2001 to 2014 to examine how 'common ownership' — where particular investors hold stakes in multiple airlines (or large stakes) — affects prices. The conclusion was simple: the more the same investor owned multiple firms in an industry, the higher the average fare on those routes — roughly 3–7% higher.

The related debate has spread to other oligopolistic industries. Banking is structurally prone to common ownership effects. A 2022 study on "ultimate ownership and bank competition" found that regions of the U.S. with higher levels of common ownership had higher bank account maintenance fees and lower deposit interest rates. This suggests common ownership can directly increase consumers' financial costs.

There is growing concern that common ownership may even weaken the drive for innovation. Economists describe this as the 'business-stealing effect.' If one firm introduces disruptive innovation that upends the market, its success can steal market and profits from competitors. Market tension of this kind incentivizes firms to move faster and more boldly.

But if several competitors are commonly owned by the same investor, the calculation changes. For such an investor, one firm's success leading to another's failure is merely internal bleeding. From the portfolio perspective, gains and losses may cancel out, so investors may prefer stable returns over risky innovation. Firms may read these signals and shy away from bold R&D investments that deviate from the status quo.

There is a different perspective. A new study by Jose Azar and Javier Vives, published last January, "Reassessing the Anticompetitive Effects of Common Ownership," moves the debate to an 'inter-industry effects' frame. They question the simplistic view that "common ownership always weakens competition."

The key is the presence of 'universal owners.' The so-called 'big three' own stakes not only in airlines but also in hotels, rental cars, and travel agencies that benefit when airfares fall. From their perspective, strategies that maximize the overall portfolio may instead favor lower airfares to stimulate consumption and boost other industries. This challenges the hypothesis that common ownership necessarily leads to price increases.

There are also alternative views on innovation. Some research suggests common ownership can play a positive role by internalizing 'technology spillovers.' It could coordinate overlapping research among firms and encourage collaboration in similar technological areas, improving R&D efficiency at the industry level. Rather than universally suppressing innovation, common ownership may favor 'exploitative innovation' that improves and commercializes existing technologies over 'exploratory innovation' that pursues entirely new technologies.

Regulators' antitrust dilemma

Separate from academic debate, regulators around the world are taking the issue seriously. In the U.S., the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) are beginning to consider common ownership as a new regulatory target.

This was made clear in a joint filing the DOJ and FTC submitted to FERC (the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission) last April. The filing explicitly identified three main channels through which common ownership — even via small equity stakes — could harm market competition: influence exertion, weakening of competitive incentives, and facilitation of information exchange.

Jonathan Kanter, head of the DOJ's Antitrust Division, said, "Minor equity stakes and common ownership create links among competing firms that can distort incentives for firms that should act independently," adding, "We will closely monitor the market effects of such structural links."

Despite strong government warnings, decisions in practice reflect complex realities. A representative example is FERC's recent decision to extend by three years a comprehensive approval that allows BlackRock to hold up to 20% of U.S. electric utility companies' equity. Observers say this decision starkly illustrates the tension between the principle of 'protecting competition' and the practical need for 'stable capital supply for industry development.' FERC judged that BlackRock's capital is essential for the stability and development of the U.S. energy industry.

FERC Chairman Mark Christie stated in an April filing, "Public utilities must raise the capital needed for massive investments, and much of that capital is now owned or managed by large asset managers," adding that this is an economic reality.

As regulatory pressure mounted, the 'big three' sought internal remedies to ease concerns about concentrated voting power. The result was the 'Voting Choice' or 'pass-through voting' program. This returns the voting rights that asset managers exercised to the ultimate owners of the fund assets — the end investors.

Larry Fink, BlackRock's chairman, wrote in this year's shareholder letter, "We are working toward a future where all investors can participate in vote decisions if they choose," and described, "'Voting Choice' is an innovation that allows the clients who are the true owners of the assets we manage to be much more directly involved in corporate governance."

According to BlackRock, as of June 30 its 'Voting Choice' program had about $784 billion of institutional investor assets registered. The effect of vote dispersion has also appeared. According to Vanguard's data released this year, none of the individual voting policy options chosen by program participants received more than 35% of selections.

In Korea, the National Pension Service overwhelms the U.S. 'big three'

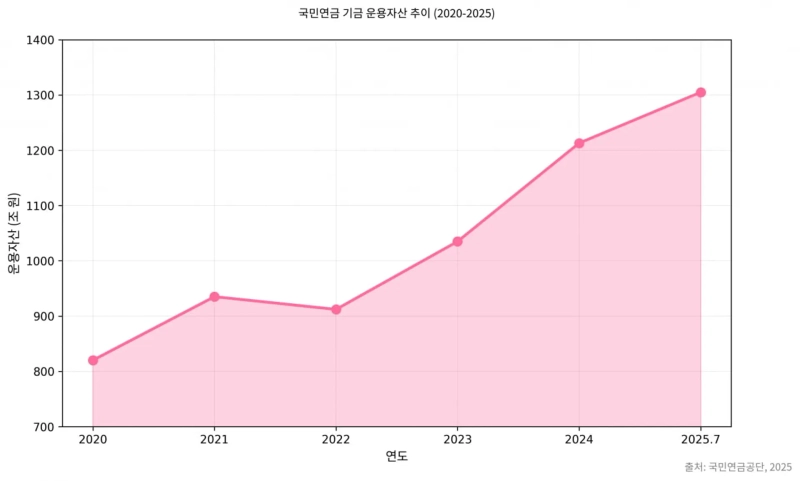

Observers say the U.S. common ownership debate has implications for the Korean market. Korea has a single institutional investor that surpasses the 'big three' in sheer dominance: the National Pension Service (NPS). The NPS is the largest single investor in the domestic stock market and the largest 'common owner' holding stakes across many competing firms.

The NPS's standing is absolute. As of the first quarter, its assets under management amounted to 1,227 trillion won. As of the end of August, its domestic equity holdings stood at 196.3 trillion won. This massive capital has been invested simultaneously across representative competing companies in key domestic industries. In semiconductors, it is a major shareholder of Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix. In the automobile industry, it is a major shareholder of Hyundai Motor and Kia.

In most major domestic oligopolistic industries — telecommunications, retail, and petroleum — the NPS is a major shareholder of key competitors. This structure makes the NPS a 'common owner' of a different magnitude than the U.S. 'big three.' The NPS's ability to exercise voting power directly as a single entity means its influence density is much higher.

Analysts say there is no clear evidence yet that the NPS's common ownership has distorted domestic industries. Nonetheless, with the NPS's influence growing, there is a need to continuously review how its voting principles and shareholder guidelines impact market competition.

[Global Money X-file traces important but little-known flows of global money. For convenient delivery of essential global economic news, please subscribe to the reporter page]

Reporter Joo-wan Kim kjwan@hankyung.com

Korea Economic Daily

hankyung@bloomingbit.ioThe Korea Economic Daily Global is a digital media where latest news on Korean companies, industries, and financial markets.

![[Analysis] "XRP risks repeating the 2022 rout…most short-term investors in the red"](https://media.bloomingbit.io/PROD/news/845f37bb-29b4-4bc5-9e10-8cafe305a92f.webp?w=250)

![[Exclusive] “Airdrops also taxable”... Authorities to adopt a ‘comprehensive approach’ to virtual assets](https://media.bloomingbit.io/PROD/news/4bde9dab-09bd-4214-a61e-f6dbf5aacdfb.webp?w=250)