"Turning 100 million won into 5 billion won with your own money"… Investors flock, 'fear spreads' [Global Money X-File]

Summary

- The global financial market has reported that the spread of arbitrage trading and high-leverage strategies is significantly increasing systemic risk and market volatility.

- It stated that across finance, blockchain, real estate, and other areas, investment and subsidy hunting exploiting regulatory gaps are actively taking place.

- It said that the expansion of this arbitrage economy can act as an investment risk factor, causing short-term profit opportunities as well as structural costs and spillover risks.

From subsidy hunting to regulatory arbitrage… 'Arbitrage economy' shaking the global economy

Recently, an 'arbitrage economy' that maximizes profits by exploiting complex related systems rather than innovation is emerging. Factors include geopolitical fragmentation, the revival of large industrial policies, market hyper-financialization, and the acceleration of algorithmic technologies. Critics say this method of value creation distorts the incentive structure of the global economy.

Targeting the 'rules of the game'

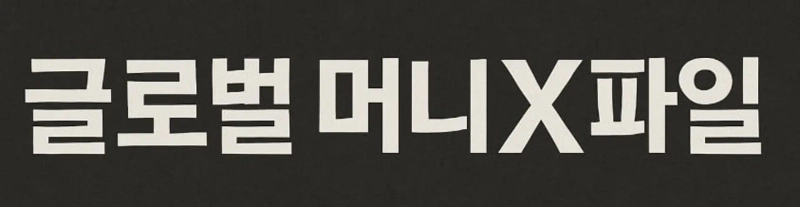

On the 17th, Reuters reported that U.S. banks borrowed $1.5 billion in one day on the 15th from the U.S. central bank's short-term lending window (Standing Repo Facility·SRF). Reuters explained the borrowing reasons as "corporate tax payments, U.S. Treasury debt settlement deadlines, etc." Some analysts said that a sharp increase in arbitrage demand related to U.S. Treasury 'basis trades' put pressure on short-term funding markets.

A basis trade is buying U.S. Treasury cash (the actual bond) while selling Treasury futures (contracts to buy in the future). It earns money from the small price difference between cash and futures. It is one of the representative 'arbitrage economy' strategies. The problem becomes larger when 'leverage' is applied.

Investors borrow against Treasuries as collateral to magnify trade sizes by tens of times. It's like turning 100 million won of one's own money into operating 5 billion won. If this strategy works well, large profits are made, but if the market moves even slightly, losses can snowball. At the same time, many funds unwinding positions can shake the entire market.

That happened in early 2020 when COVID-19 spread. As U.S. Treasury prices swung, investors simultaneously liquidated trades, and U.S. Treasury yields spiked in a short period. Eventually, the Fed had to inject $1 trillion in emergency funds to stabilize the market. Recently, such risks have been growing again as SRF demand surges. The European Central Bank (ECB) warned that "given that U.S. Treasuries are considered the global risk-free asset, a spike in volatility from position unwinds could transmit to other asset classes and countries."

An era dominated by 'system gaming'

The current global 'arbitrage economy' is said to run on four major drivers: geopolitical fragmentation, the revival of large industrial policies, market hyper-financialization, and the acceleration of algorithms. These four forces amplify each other and increase momentum.

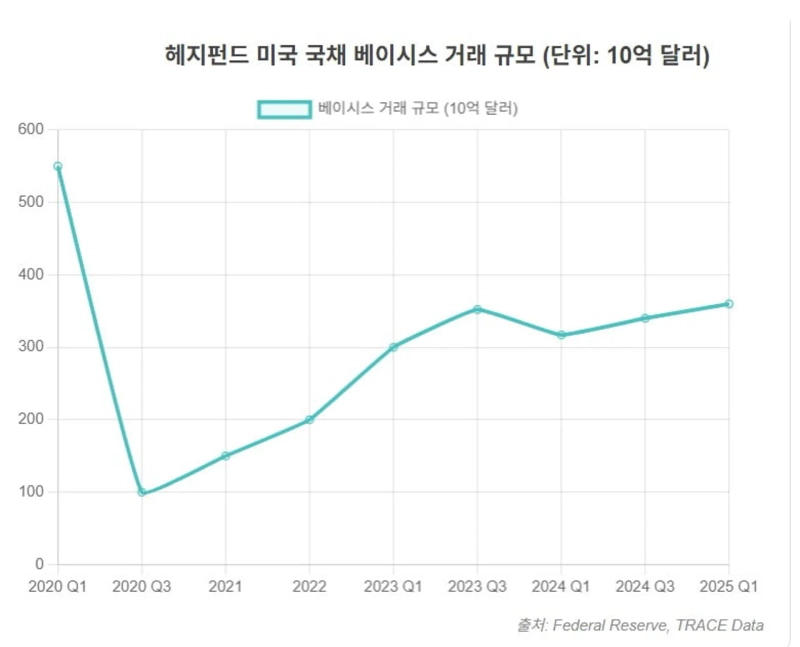

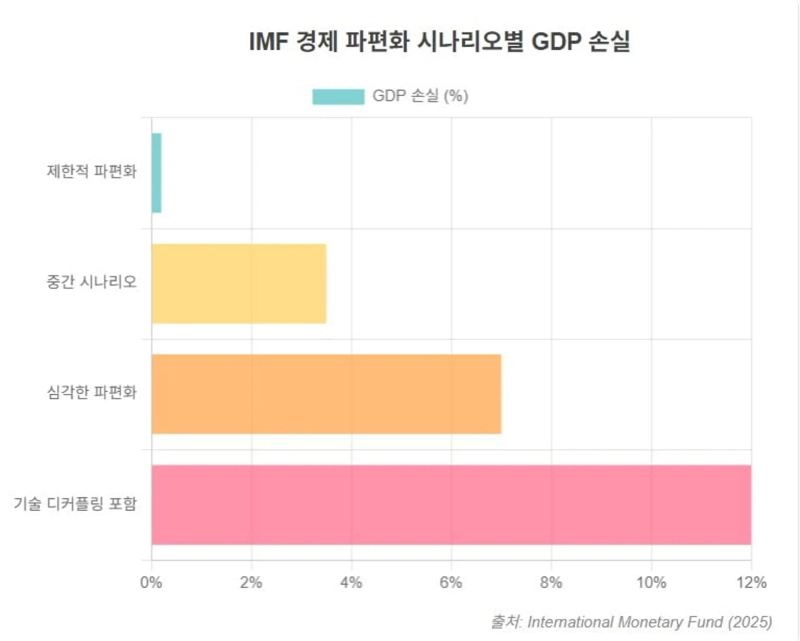

Geopolitical fragmentation mainly appears as recent U.S.-China competition. U.S.-China hegemonic competition and the spread of protectionism have created differing tariff and regulatory levels by country. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) report 'High Uncertainty and an Unknown World,' about 3,000 trade restrictions were imposed worldwide in 2023. That's nearly three times the number in 2019.

As a result, so-called 'jurisdictional arbitrage' opportunities have increased. The IMF warned that such fragmentation could, in the worst case, cause production losses equivalent to 7% (about $7.4 trillion) of global GDP. IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva said, "Uncertainty imposes costs. In a world where tariff rates fluctuate, planning becomes difficult. The result is investment decisions are delayed."

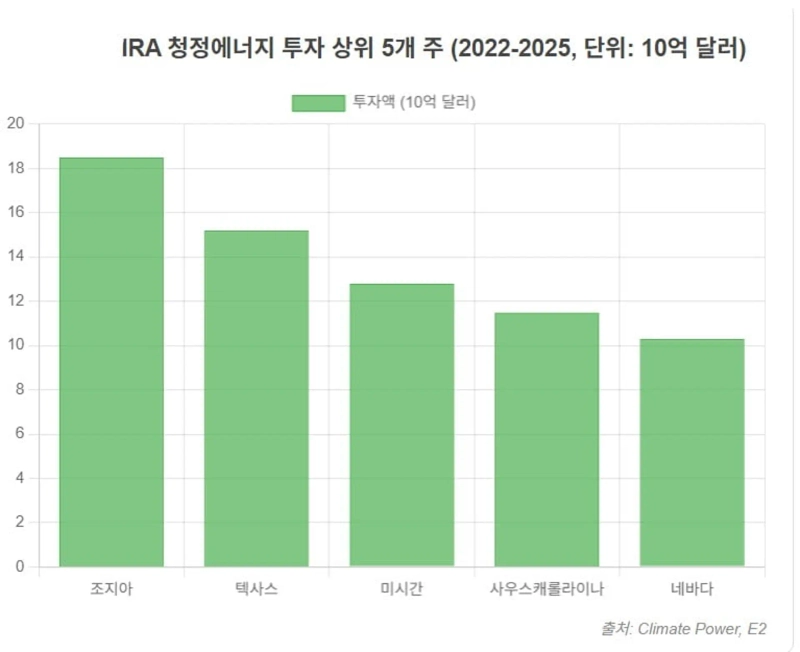

The 'big bang' of industrial policy is also a major driver of the 'arbitrage economy.' Large subsidy policies such as the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the EU's responses are filled with complex eligibility requirements and regulations spanning thousands of pages. This unintentionally opened a new market of 'subsidy hunting.'

Hyper-financialization is also a factor in the 'arbitrage economy.' Strengthened bank regulations after the global financial crisis moved complex trading strategies and risks to relatively less-regulated nonbank financial intermediation, the so-called 'shadow banking' sector. In this process, ultra-high-leverage arbitrage markets like U.S. Treasury basis trades expanded rapidly.

The final engine of the 'arbitrage economy' is algorithmic acceleration. Artificial intelligence (AI) and high-performance computing have made it possible to capture and execute fleeting arbitrage opportunities that humans cannot perceive at scale, not only in financial markets but also in digital advertising, blockchain, and other areas. As these four drivers combine, arbitrageurs emerge as solvers of the complexity.

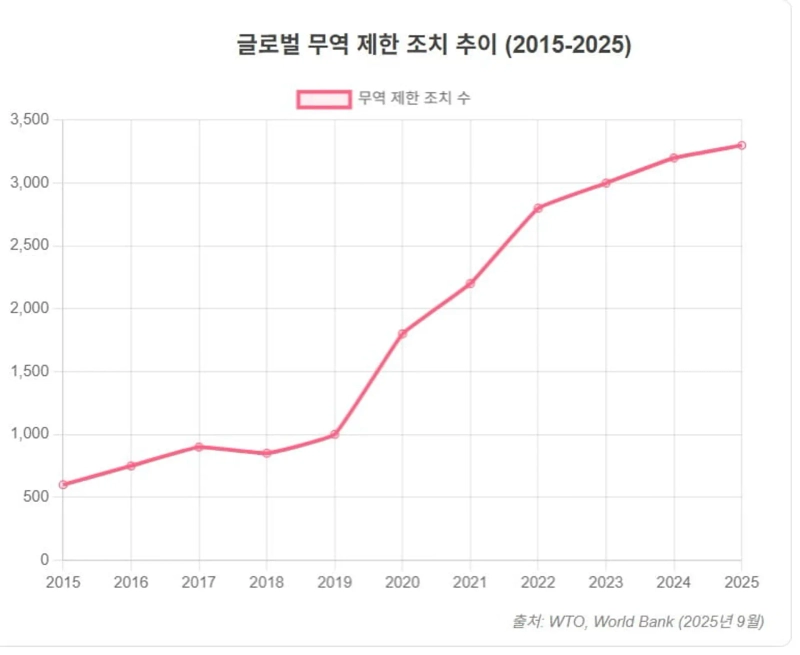

As the 'arbitrage economy' grows, talent is also flowing into the related markets. Typically, the long-term vitality of an economy depends on where talent heads. Recently, some talent appears to have chosen the path of accumulating wealth by exploiting gaps in arbitrage economy systems rather than pursuing innovation.

U.S. Ivy League heading to Wall Street

According to a career survey of Harvard University graduates, 21% of this year's graduates went into finance and 14% into consulting. Finance, technology, and consulting together account for more than half of all graduates. This concentration is driven by overwhelming compensation structures. According to the New York State Comptroller, last year New York's securities industry's bonus pool surged 31% year-on-year to $47.5 billion. The average bonus was $244,000. This shows that elite groups concentrated on transferring and intermediating wealth, strengthening so-called 'rent-seeking' cycles.

The financial industry, which absorbed massive human capital, is criticized for insufficient social value creation. According to Thomas Philippon of New York University, the 'unit cost' of intermediating $1 from savers to borrowers has remained around 2% over the past 130 years despite dramatic advances in technology. Professor Philippon pointed out, "The tremendous progress in information technology over the past decades has not led to a reduction in financial intermediation costs."

The arbitrage economy does not arise in a vacuum. It grows on soil of well-intentioned government policies, structural market inefficiencies, and technical loopholes. The fine gaps in complex regulations and institutions are costs for some, but for others they become 'legitimate' opportunities that generate massive profits.

Subsidy and regulatory arbitrage

Government subsidies are representative. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) injected $369 billion in green subsidies. This opened a huge global 'subsidy hunting' market. The consumer electric vehicle tax credit under the IRA included strict origin rules, but the commercial vehicle tax credit did not have the same rules.

The U.S. Treasury allowed a $7,500 tax credit if an automaker provided a vehicle in a lease form and considered it 'commercial.' This opened a huge loophole. Some foreign manufacturers ran lease programs for their EVs that did not meet origin rules to indirectly exploit the subsidy system.

But these windows of arbitrage are closing. The 'One Big Beautiful Bill Act' that went into effect on July 4 targeted such subsidy leakage. Under this act, the commercial electric vehicle tax credit will end for acquisitions after the 30th of this month.

The European Union's emissions trading system (ETS) showed a similar pattern. When the EU included shipping in the ETS from last year, a regulatory evasion strategy called 'port hopping' emerged. Voyages between EU and non-EU ports are subject to purchasing allowances for 50% of emissions. To avoid this, companies increasingly called briefly at nearby non-EU ports (such as Tangier Med in Morocco) just before the final destination to transfer cargo.

Technological advances have expanded the stage for arbitrage into digital spaces. Blockchain is a representative area where algorithms exploit system loopholes to extract huge value. On public blockchains like Ethereum, a user's transaction request stays briefly in a public waiting area called the 'mempool' before being finally recorded on a block.

MEV (maximal extractable value) bots view this information in advance and pay higher fees to insert their transactions or change order. A bot that spots a large buy order buys first and then sells right after the price rises to capture the spread. The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) noted in a July report that since 2020 only on Ethereum, billions of dollars of value have been extracted via MEV.

Korea's 'arbitrage economy'

Korea also has arbitrage that exploits policy design loopholes. The housing market's LTV (loan-to-value ratio) and DSR (debt service ratio) are representative. LTV and DSR can increase leverage without improving repayment ability by using exceptions, maturities, and industry boundaries. When bank mortgage lending tightens, a balloon effect occurs where borrowers move to products excluded or relaxed from DSR (jeonse, interim payment, some policy loans) or to secondary financial institutions and business loans where regulation is looser.

As a result, instead of productivity or income, the gaps in regulations are traded like 'prices' to increase limits and returns. This also meets the criteria of arbitrage because risks and costs are shifted to the system. A paradox of regulation also appears. DSR regulation, which limits principal and interest payments relative to income, is not a big barrier for high-income people. But low-income citizens and young people are blocked by DSR rules and find it harder to get opportunities to own a home.

In energy policy, splitting solar REC (renewable energy certificate) subsidies was problematic. Some large developers registered a power plant on paper as multiple smaller ones and improperly collected large subsidies intended for small operators. This is a representative case of 'subsidy hunting' that abused well-intentioned policy.

Reporter Joo-wan Kim kjwan@hankyung.com

Korea Economic Daily

hankyung@bloomingbit.ioThe Korea Economic Daily Global is a digital media where latest news on Korean companies, industries, and financial markets.

![[Exclusive] KakaoBank meets with global custody heavyweight…possible stablecoin partnership](https://media.bloomingbit.io/PROD/news/a954cd68-58b5-4033-9c8b-39f2c3803242.webp?w=250)