Big payoff if you win, total loss if you lose… Where 'big players' flock with money [Global Money X-File]

Summary

- The global litigation finance (TPLF) market is described as uncorrelated with market fluctuations and attracting institutional investors with high internal rates of return (IRR) and returns on invested capital (ROIC).

- TPLF investment is characterized by a high-risk, high-return structure, 'uncorrelated asset' traits, and large funds plus data-driven analytical capabilities as key competitive advantages.

- Korean companies are said to be constantly exposed to international litigation risks such as patent disputes due to regulatory gaps and overseas TPLF.

TPLF investing in litigation

Uncorrelated with market fluctuations

Popular with institutional investors

Recently, so-called 'litigation finance,' in which the outcomes of legal disputes are traded like stocks or bonds, has been drawing attention in global financial markets. This is because huge capital on Wall Street has been directly investing in corporate patent litigation and antitrust disputes. Analysts say such investment is shaking up how judicial systems operate and reshaping corporate risk landscapes.

A new playground for big capital: TPLF

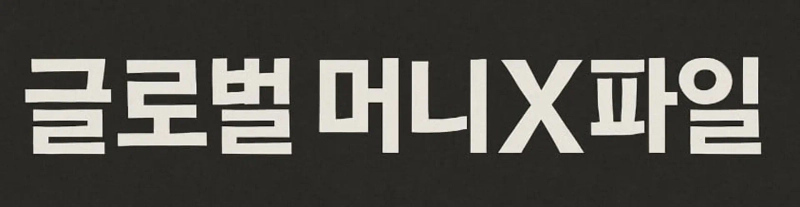

On the 22nd, U.S. market research firm 'Research Nester' said the global litigation finance market is expected to grow from more than $19.3 billion this year to $53.2 billion by 2035. According to U.S. crisis management consulting firm 'Marathon Strategies,' there were 135 so-called 'nuclear verdicts' last year involving awards of more than $10 million. The related total litigation amount reached $31.3 billion. It was a record high, up 52% year-on-year.

This is due to the growth of the multibillion-dollar industry known as 'third-party litigation funding (Third-Party Litigation Funding· TPLF).' The core structure of TPLF is that external investors—hedge funds, private equity funds, and even sovereign wealth funds—cover the substantial legal costs of litigants (mainly plaintiffs) and, if they win, take a portion of settlements or awards as returns.

A key feature of TPLF is the so-called 'non-recourse' condition. If the lawsuit is lost, the investor loses the entire investment and cannot demand repayment from the plaintiff. This high-risk, high-return structure effectively turns legal claims into assets similar to venture capital (VC) investments. TPLF is a way of commodifying the "transfer and redistribution of risk." It shifts the financial risk of litigation (cost losses when losing) that plaintiffs or lawyers traditionally bore to specialized capital market investors, turning litigation itself into a financial product.

The uncertain outcome of 'winning' or 'losing' a lawsuit has attributes similar to options or derivatives in financial markets. The non-recourse condition creates a structure where investors absorb all the downside risk of a lawsuit in exchange for pursuing high potential returns. Some analysts say this represents a fundamental paradigm shift, combining the logic of capital markets with the legal services market.

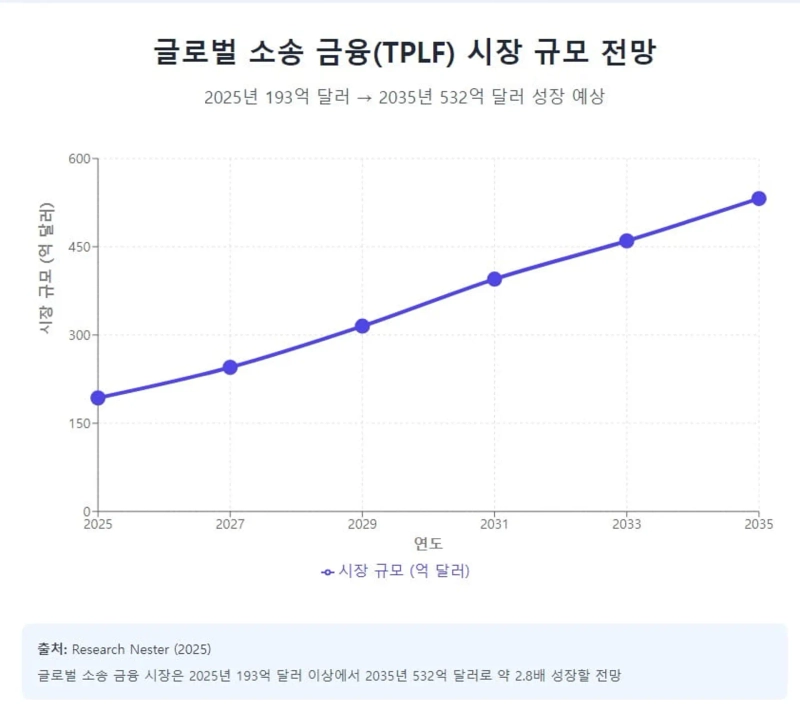

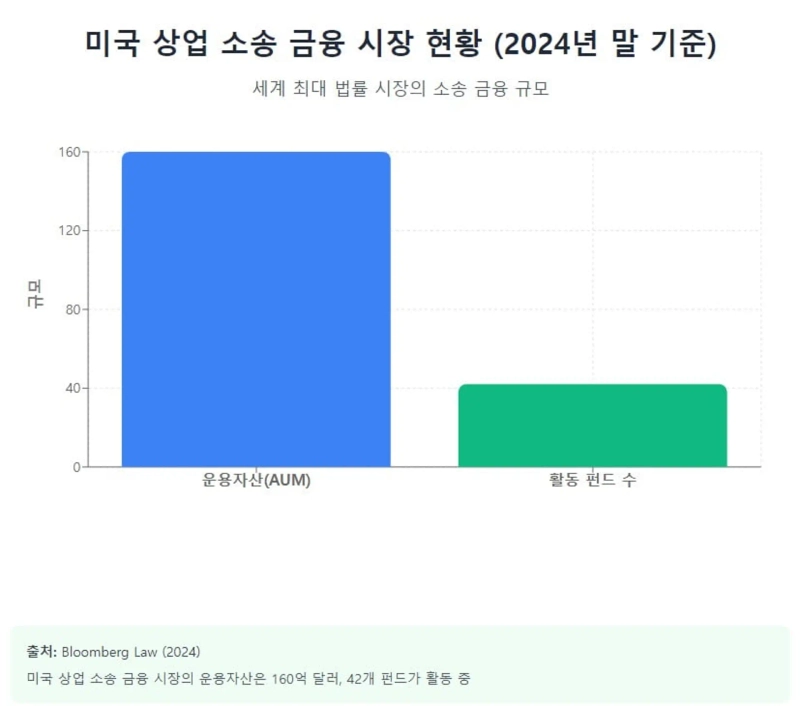

The United States, the world's largest legal market, is leading this growth. According to analysis by Bloomberg Law this year, assets under management (AUM) in the U.S. commercial litigation finance market reached $16 billion at the end of last year. Active funds were counted at 42. Research Nester forecasts that North America will remain the largest regional market, accounting for 37.2% of the total market by 2035. The fastest-growing region is expected to be the Asia-Pacific.

One reason institutional investors are interested in the litigation finance (TPLF) market is its characteristic as an 'uncorrelated asset.' An uncorrelated asset is one that has little relation to assets that rise and fall with economic conditions, such as stocks or bonds. In other words, the value of these assets is not greatly affected whether the economy is good or bad.

The reason litigation finance fits this category is simple. Lawsuit outcomes are determined by the legal merits of the case and the strength of evidence, not by macroeconomic factors like interest rates or the economy. From an investor's perspective, it is seen as a new investment avenue where returns can be expected regardless of market volatility.

For this reason, even if the stock market plunges due to financial crises or recessions, the value of TPLF assets is relatively less affected. Investors thus expect TPLF to play an "insurance-like" role in reducing portfolio volatility and increasing stability. In fact, industry reports indicate that the average internal rate of return (IRR) on TPLF investments is around 25~30%. It is viewed as an attractive investment because of its high returns despite high risks.

Leveraging large-scale data and capital

The global litigation finance (TPLF) market is led by several large firms. Representative companies such as Burford Capital and Omni Bridgeway account for much of the market. Burford, in particular, is called a 'barometer' showing the direction of the entire market. Burford reported revenue of $191.28 million in the second quarter of this year, about 17% above market expectations.

The most notable case was the YPF nationalization lawsuit against the Argentine government. In that case, Burford secured a verdict of as much as $16.1 billion. In June, a U.S. federal court in New York ordered Argentina to transfer more than 51% of YPF's shares to enforce the judgment, revealing the enormous potential of litigation finance. As of the first half of this year, Burford recorded a return on invested capital (ROIC) of 83% and an internal rate of return (IRR) of 26%.

These leading firms concentrate investments on large-scale commercial disputes with high added value. Patent and intellectual property (IP) litigation, characterized by massive legal costs and high potential awards, is a core investment target. According to Bloomberg Law, funding for patent litigation accounted for 32% of allocations last year. Recently, shareholder derivative suits related to ESG and class actions over data breaches have also emerged as new investment targets.

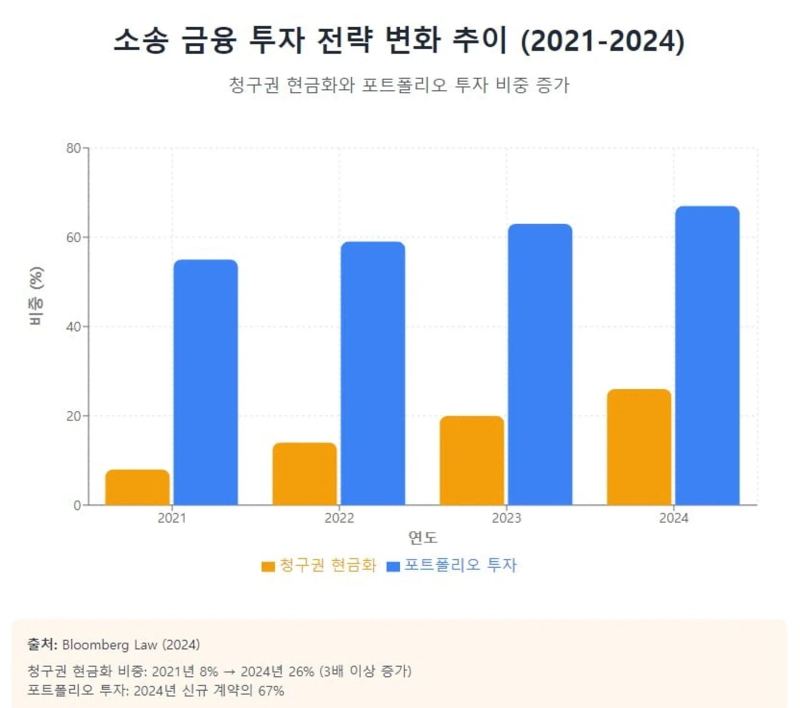

As the market matures, TPLF investment strategies are diversifying. The most notable change is the surge in 'monetization' of claims. This is a method in which a company sells its litigation claim to a litigation funder and secures cash immediately regardless of the lawsuit outcome. Simply put, it is selling 'future litigation proceeds' for cash now.

According to Bloomberg Law, the share of such transactions rose from 8% in 2021 to 26% in 2024—more than tripling. This shows that companies prefer securing immediate cash flow and reducing uncertainty rather than enduring long litigation processes.

Also, rather than investing in a single case as before, 'portfolio investing' that bundles multiple lawsuits is increasing. About 67% of new contracts are made in this way, meaning strategies to diversify risk and stabilize return structures are becoming more sophisticated.

The TPLF market is increasingly becoming a game favoring large players. The core is scale and data. A single failed litigation can lead to significant losses. You need broad diversification across types and regions to offset individual loss risk. That strategy requires large capital, so big funding companies naturally have an advantage.

To predict litigation outcomes more accurately, vast historical data is essential: who won, what evidence worked, judge and jury tendencies, and enforcement success rates. This data is an asset accumulated through money and time, so large players lead here as well.

Jonathan Molot, co-founder and CIO of Burford Capital, said in a shareholder letter this year, "Our asset modeling is based on massive proprietary data," adding, "This allows us to precisely measure the risks and potential returns of the litigations in which we invest." He added, "We are not simply lending money; we are a technology-driven financial firm that quantitatively analyzes and prices legal risk."

How litigation is changing industrial ecosystems

The spread of TPLF has affected competitive dynamics and risk management across industries. Technology-intensive sectors such as semiconductors, biotech, and telecommunications are representative. In IP disputes that require huge costs, TPLF provides financially constrained small firms or non-practicing entities (NPEs) with the financial "firepower" to go head-to-head with large corporations. This can function positively by protecting technological innovation and checking market monopolies.

On the other hand, for defendant major corporations, risks increase exponentially. In the past, opponents might have given up litigation due to financial pressure; now they can back long legal fights with huge capital. This escalates disputes from pure legal arguments to 'capital wars' against specialized financial institutions, significantly increasing legal budgets and managerial uncertainty.

In the recent Intel vs. VLSI (a Fortress affiliate) patent case, a Texas federal jury recognized Fortress's "common control" structure behind VLSI. That ruling worked in Intel's favor and raised the possibility that past massive verdicts that VLSI received in the billions could be overturned or weakened. When complex litigation structures involving TPLF capital are exposed, defendant companies can attack that structure as a defense strategy. Once who is truly funding and controlling the case is proven, the litigation outcome and settlement terms can change.

In cross-border international arbitration, TPLF has already become a common funding mechanism. Since Singapore and Hong Kong legalized TPLF in international arbitration in 2017, the Asia-Pacific market has grown rapidly. This coincides with the trend of intensified global supply chain disputes.

Raymond van Hulst, CEO of global litigation specialist Omni Bridgeway, said on a recent conference call, "Funding demand for international arbitration cases is exploding in the Asia-Pacific region, especially centered on Singapore and Hong Kong," adding, "This is due to increased regulatory clarity in those jurisdictions and intensifying global supply chain disputes."

Rise of the 'legal quant'

The growth of TPLF has also triggered changes in the legal services industry. The essence of TPLF is risk management. Investment success hinges on how accurately one can predict litigation outcomes. This demand has driven the growth of a 'litigation analytics' industry that combines AI and big data.

Companies such as Lex Machina and Bloomberg Litigation Analytics analyze decades of case law, court records, and judgment data with AI to provide quantitative data such as a particular judge's past ruling tendencies, a law firm's win rates by specialty, the average litigation duration for similar cases, and the expected range of damages.

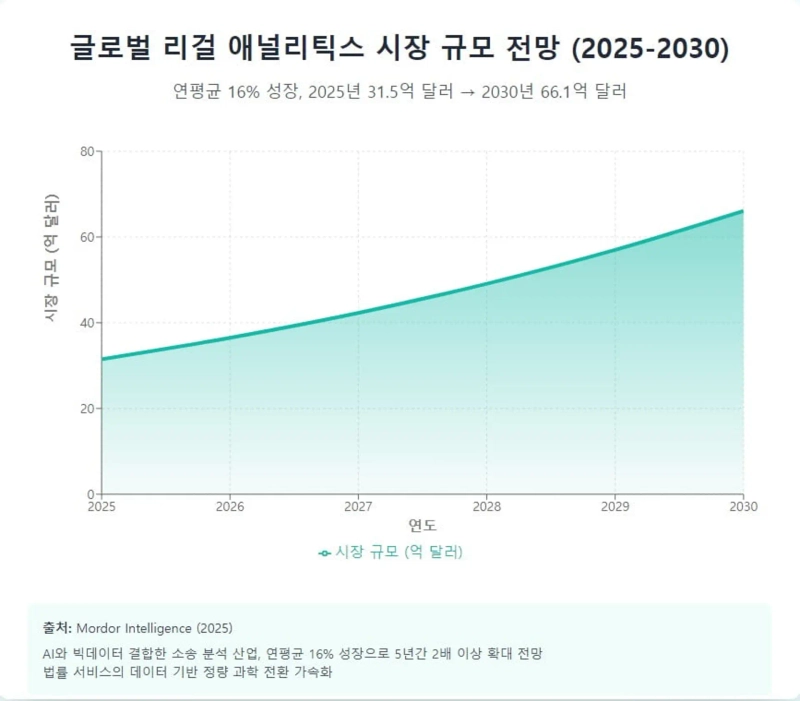

According to market research firm Mordor Intelligence, the legal analytics market is estimated at $3.15 billion this year and is projected to grow at an average annual rate of 16% through 2030. The AI software market for the legal field is also expected to reach $2.42 billion by 2025 with a high growth rate.

These changes are shifting traditional legal analysis—once reliant on lawyers' intuition and experience—into a domain of data-driven quantitative science. Just as quants in finance construct investment strategies with complex mathematical models, a new expert group called 'legal quants' is emerging in the legal market, designing litigation strategies and making investment decisions based on data.

Ellen Chen, head of data science at Lex Machina, said in a damages trends report released in July, "Our data shows that federal court damages have risen recordly over the past two years, and especially that jury verdict amounts have become more volatile," adding, "Now, risk assessment based on data analysis is not an option but a necessity for litigation strategy formation."

One macro effect of TPLF on industry is what analysts call the deepening of 'social inflation.' This refers to the overall rise in insurance premiums caused by increased litigation costs and awards. As TPLF-funded lawsuits prolong and lead to large verdicts, insurers' loss ratios worsen, which is ultimately passed on as higher liability premiums for all companies in a vicious cycle.

Justice served or system disruption?

The growth of the TPLF industry has fueled controversy because it produces both positive and negative effects. On the positive side, TPLF is seen as a tool that expands 'access to justice.' Faced with astronomical litigation costs, individuals or small companies that could not challenge large corporations' illegal acts can acquire the financial "weapons" to sue through TPLF.

On the other hand, TPLF may act as a catalyst for abuse of litigation. The sole goal of TPLF investors is to maximize investment returns. They decide investments based purely on win probability and expected returns rather than public interest or justice. Critics argue that lawsuits with low chances of success or limited social value may be indiscriminately filed, imposing huge defense costs on defendants and increasing society's overall legal expenses.

Judicial ethics issues have also been raised. There is concern that TPLF may prioritize funders' returns over plaintiffs' best interests and exert undue pressure in settlement decision-making. Nora Freeman Engstrom, a professor at Stanford Law School, wrote in 'Legal Ethics: The Plaintiffs' Lawyer' that "TPLF certainly has the positive effect of increasing access to justice, but it contains the possibility that litigation funders' interests will conflict with plaintiffs' best interests," and "there is an ethical dilemma where funders may exert pressure to make unreasonable demands or to refuse early settlement in the settlement decision process."

Recently, the U.S. legal community has focused on the surge in 'nuclear verdicts' exceeding $10 million. TPLF critics point to litigation finance as a main cause of this phenomenon. They argue that when TPLF capital is involved, plaintiffs can prolong lawsuits without funding pressure and refuse settlements to push cases to trial, increasing the likelihood of large awards.

Evan Greenberg, CEO of the largest U.S. commercial insurer Chubb, wrote in a Wall Street Journal op-ed that "TPLF is 'parasitic' capital that prolongs litigation and makes settlements difficult, exponentially increasing social costs," and strongly criticized that "the premium increases caused by this are ultimately passed on to all consumers and companies."

Emerging as a national security risk

There are also concerns that the TPLF industry could pose potential threats to national security. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Institute for Legal Reform (ILR) and U.S. think tank the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) have repeatedly raised scenarios where sovereign wealth funds or state-owned enterprises linked to strategic competitors such as China or Russia could secretly fund U.S. litigation via TPLF. A U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report also mentioned that the Department of Justice is reviewing foreign funding in patent litigation.

Analysts say such concerns could materialize through two routes. First, the discovery process in U.S. litigation could be abused. This procedure allows plaintiffs to request relevant materials from defendant companies for use as evidence. But with the increase in 'litigation funding' involving foreign capital, there is growing worry that discovery could become a channel for leaking sensitive corporate information.

For example, if a plaintiff funded by foreign funders sues semiconductor, AI, or biotech companies, they could request vast amounts of internal design documents, source code, and research data. The problem is that core technologies and trade secrets could flow to foreign funders through this process.

There is also concern that TPLF could be exploited as an 'asymmetric attack tool.' Hostile-country capital could use environmental groups or consumer organizations to file successive lawsuits against key U.S. industries—such as energy or defense companies. In this case, the goal would not simply be monetary awards but using the litigation process itself to damage corporate reputations and hamper operations.

James Andrew Lewis, senior vice president at CSIS, said in a policy report last month, "There is no clear evidence that a foreign government has used TPLF for economic espionage, but absent regulation the possibility always exists," adding, "This is a gray-area security threat that urgently requires preventive regulation."

Korea exposed to asymmetric risks

Korea occupies a unique position where opportunities and threats from the TPLF industry intersect. The domestic market is still in its infancy due to regulatory gaps. However, Korean global companies are already directly exposed to litigation risks triggered by TPLF overseas.

There is no law in Korea that explicitly specifies whether or how commercial TPLF is permitted. This legislative gap acts as an obstacle to the growth of the domestic TPLF market. The prevailing legal view is that TPLF may conflict with existing legal frameworks, such as prohibitions on 'litigation trusts' or 'partnership in legal affairs' under the Attorney-at-Law Act, and the prohibition of litigation trusts under trust law. Analysts say that TPLF investment in domestic civil litigation is practically difficult due to legal uncertainty.

Korean companies are major targets of overseas TPLF. Korea's leading export industries—semiconductors, batteries, automobiles, and biotech—compete fiercely in global markets and are constantly exposed to various international disputes such as patent infringement, antitrust, and product liability.

[Global Money X-File covers important but little-known flows of global money. To conveniently receive necessary global economic news, subscribe to the reporter page]

Reporter Kim Joo-wan kjwan@hankyung.com

Korea Economic Daily

hankyung@bloomingbit.ioThe Korea Economic Daily Global is a digital media where latest news on Korean companies, industries, and financial markets.

![[Exclusive] FSS to examine ZKsync coin that surged '1,000%' in three hours](https://media.bloomingbit.io/PROD/news/1da9856b-df8a-4ffc-83b8-587621c4af9f.webp?w=250)