'Not "money printing" but is it?… The real meaning of the Fed's short-term bond purchases [Bin Nansa's Flawless Wall Street]'

Summary

- The Fed said it would start buying short-term Treasuries (RMP) earlier and at a larger scale than expected, which many in the market interpret as a de facto Quantitative Easing (QE).

- With the U.S. Treasury increasing short-term issuance to avoid rising long-term yields, the Fed's short-term purchases could effectively support large Treasury financing, analysts say.

- Wall Street experts recommend rebalancing investment strategies to increase allocations to equities and alternative/real assets (gold, silver, Bitcoin, etc.) in light of rising government debt and inflation risks.

At the FOMC that concluded on the 10th (local time), the story the market paid most attention to was not the interest rate cut everyone had expected. It was the Fed's announcement that, starting on the 12th—sooner and at a larger scale than Wall Street had expected—it would begin "Reserve Management Purchases (RMP)" by buying about $40 billion a month of short-term Treasury securities.

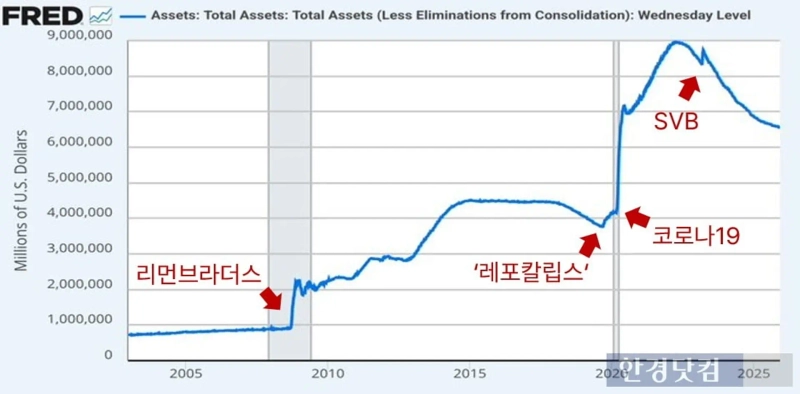

Having ended three and a half years of Quantitative Tightening (QT) on the 1st of this month, the Fed has officially signaled the resumption of balance sheet expansion. Markets erupted into debate over whether this amounted to a de facto Quantitative Easing (QE). Some argue that RMP, which buys short-term securities, is fundamentally different from QE, which buys long-term securities to lower long-term rates and stimulate the economy; others argue that, in effect, it will have similar results by supporting large Treasury financing.

Of course, the Fed insists on the former. Still, many risk-asset investors are in the latter camp, expecting a "liquidity party." Further, voices on Wall Street are growing louder advising investors to rework strategies, saying the era of "fiscal dominance," where monetary policy is subordinated to fiscal policy, has begun.

Reserve Management Purchases (RMP) vs Quantitative Easing (QE)

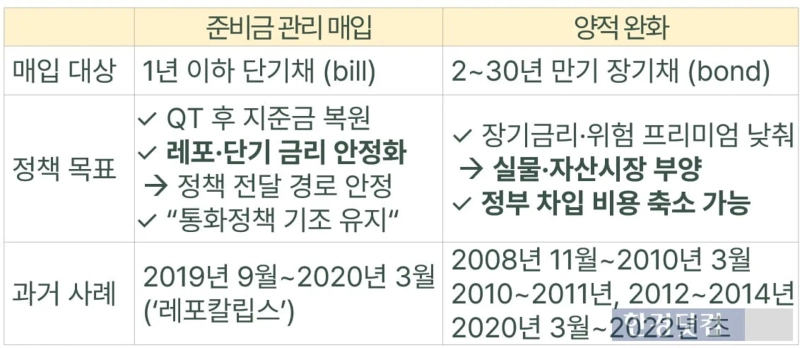

Both RMP and QE are policies in which the Fed buys assets and expands its balance sheet. But their means and goals are clearly different.

RMP is a technical measure to keep bank reserves—reduced by QT—at an appropriate level relative to the size of the real economy. It is intended to maintain the tightening stance of monetary policy at a 'neutral' level, not to shift to an easing monetary policy. To do this, the Fed buys short-term Treasuries (T-bills) with maturities of one year or less. This is fundamentally different from QE, under which the Fed buys long-term Treasuries (T-bonds) with maturities of 2–30 years as part of an easing policy to raise long-term bond prices → lower yields → expand lending and reduce risk premia → stimulate the real economy and asset markets.

In a press conference after the FOMC on the 10th, Fed Chair Jerome Powell emphasized, "Short-term purchases are completely separate from monetary policy. They are simply needed to maintain an ample level of reserves in the system," and added that they are necessary "to ensure the policy rate stays within the target range and to manage reserves to remain at a certain level because as the economy grows, demand for cash and reserves also rises."

Unlike QE, which expands liquidity and lowers long-term yields to spur real-economy investment and growth, RMP is merely about maintaining the balance sheet—like buying clothes that fit a growing child.

RMP faster and stronger than expected

The Fed's announcement of RMP at this FOMC was largely anticipated. Over the past two to three months, the market experienced repeated dollar liquidity stress. The fact that ultra-short-term market rates such as SOFR and repo rates kept jumping outside the Fed's policy rate target band showed this.

A combination of prolonged QT and declining reserves, plus large-scale short-term issuance by the U.S. Treasury, made dollar cash scarce, leading some institutions to compete to secure dollars even by offering higher rates. It was a signal that, despite abundant money in the money markets and rising broad money (M2), the plumbing that channels liquidity where needed was not functioning smoothly.

In response, John Williams, president of the New York Fed responsible for the open market operations desk, had already signaled in early November that RMP would be resumed to bolster reserves. Wall Street had expected the Fed to start buying short-term Treasuries as early as January next year at anywhere from $8 billion to $35 billion a month.

But the RMP that was actually announced came sooner and in a larger amount. The Fed moved preemptively to prepare for a surge in cash demand around year-end closings and the April tax payment period next year. Behind this was also a trauma from the 'repocalypse' in 2019, when repo rates spiked and disrupted financial markets.

The "repocalypse" refers to the September 16, 2019 episode when repo rates surged in a single day from the low 2% range to the 10% range. Corporate tax payments and large Treasury settlement flows drained reserves from the banking system all at once, causing a sudden shortage of short-term funding and a spike in rates.

At that time, the Fed was finishing a tightening cycle after about two years of QT and had just begun cutting rates; it believed reserves were adequate, but the episode showed otherwise. From then on, Wall Street began to emphasize that large banks that should lend in the repo market were reluctant to do so—even if they had cash—because of stronger post-crisis regulation and risk management.

The Fed responded by conducting RMP in October 2019 to increase reserves, buying $60 billion a month for six months—a total of $360 billion. Even then, Chair Powell said, "This is not QE in any sense. It is a technical measure to resume natural growth of the balance sheet to maintain ample reserves."

Many similarities exist with the current situation. But then came the COVID-19 crisis, and the Fed extended the maturities of the Treasuries it bought through RMP in March 2020 and ultimately resumed QE.

The Fed wants to avoid 'fiscal dominance'—"This is not QE"

Why has the Fed tried so hard then and now to block market expectations of QE? QE, which expands the central bank's balance sheet, became a core monetary policy tool after the 2008 global financial crisis, playing a decisive role in stabilizing and stimulating the economy. The same was true during COVID-19.

But the fact that the balance sheet was kept enlarged after the crisis when it should have been restored is seen by central banks and markets as a serious problem. Regardless of intent, if a central bank repeats QE too often or for too long, it risks distorting real rates and asset prices, fueling inflation, and encouraging bubbles and leverage expansion.

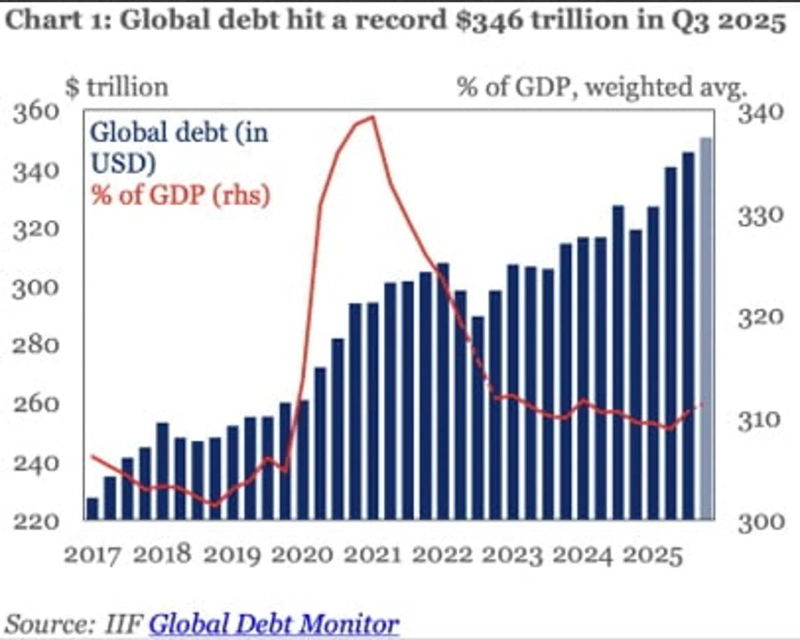

Concerns also grow over weakened central bank independence and monetary policy's subordination to fiscal policy—so-called 'fiscal dominance.' A larger central bank balance sheet means holding large volumes of government debt, which could give the government the incentive to keep issuing debt because "the central bank will buy it anyway." With the central bank as the major buyer of government debt rather than the market, fiscal discipline weakens.

This leads to larger government debt and higher inflation. Moreover, a central bank that should control inflation faces political pressure to keep rates low because of rising government interest costs. This is already a common line of attack when President Trump criticizes the Fed.

Still, the market says "de facto QE, money printing"

The central bank wants to avoid that frame. If it fails, expected inflation will rise and it will be harder to control price increases. So the Fed avoids putting QE on the table lightly and wants to demonstrate to the market that central bank independence is intact.

But the market already senses an era of fiscal dominance. It's not just an emerging-market story. The Bank of Japan has for over a decade suppressed long-term yields directly through Yield Curve Control (YCC), and during COVID-19, as government debt grew, demands for monetary policy to support that debt increased worldwide. Even under the current Trump administration, fiscal-dominant strategies have been openly pursued. This is why many investors do not take the RMP at face value and view it as a prelude to QE.

In particular, the U.S. Treasury is currently reducing long-term issuance and increasing short-term issuance to avoid a rise in long-term yields. The Fed's decision to start buying short-term Treasuries at this time is widely seen as helping the Treasury finance its debt without market-rate shocks.

Steven Blitz, chief economist at TS Lombard, said, "Short-term purchases are more about providing preemptive financial support to absorb large fiscal spending desired by President Trump and Treasury Secretary Mnuchin at low cost without market-rate shocks," adding that "it signals that the Treasury and the Fed will effectively act as one to absorb issuance the market cannot handle."

And Andreas Larsen, founder of Steno Research, criticized RMP as a "money printer," saying, "When the Treasury increases short-term issuance to suppress long-term yields and the Fed buys those short-term securities, the practical effect is the same as QE." Regardless of the policy name or intent, the interpretation is that the Fed is printing money to buy Treasuries.

Blitz warned that "given fiscal expansion and the Treasury–Fed nexus, the risk of inflation rising again is high."

How to invest in the era of fiscal dominance

Treasury Secretary Mnuchin is not the only one pressing the Fed. He is also pushing to ease regulations to restore the role of private banks in the repo and Treasury markets. The aim is to break the pathological structure in which governments and markets look to the Fed in every crisis. By easing bank regulations so the private sector can absorb more Treasuries and banks can lend more in the repo market, rates could remain low, lending and liquidity could increase, and the recovery could be driven more by the private sector—this is Treasury Secretary Mnuchin's broader vision. Of course, this assumes everything works perfectly.

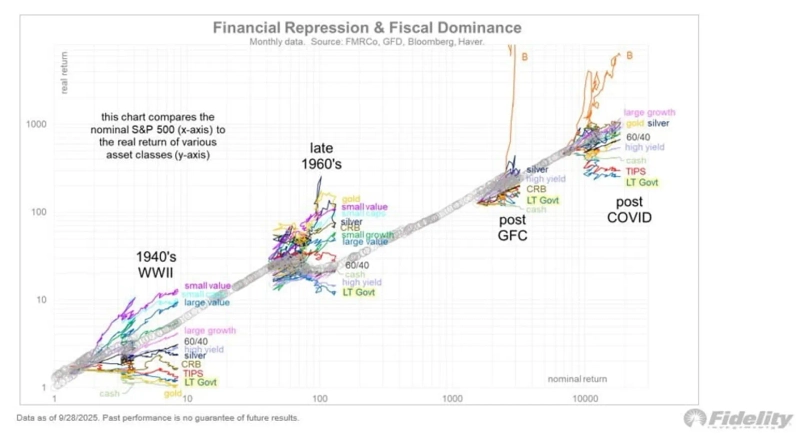

For now, the era of fiscal dominance may bring further government debt expansion and inflation concerns. If so, investment approaches must change, Wall Street says. Jurien Timmer, global macro director at Fidelity, argues that the traditional 60% equities / 40% bonds portfolio is over. He recommends a portfolio of 60% equities, 20% bonds, and 20% alternatives (gold, silver, commodities, real assets, and Bitcoin). If governments keep printing money and central banks support them, long-term bond prices are likely to fall over the long term. Even absent inflation risks, stronger growth from fiscal stimulus would also push bond prices down.

Fidelity's analysis of asset-class returns during periods of pronounced fiscal dominance after the global financial crisis and after COVID shows that long-term Treasuries and TIPS, cash, high-yield bonds, and 60/40 portfolios underperformed the S&P 500. By contrast, gold and silver, large-cap growth stocks, and Bitcoin outperformed the S&P 500.

There are many forecasts that advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and productivity increases could ultimately bring a deflationary era. But until that future arrives and is confirmed, it seems unlikely that the pace of rising government debt will be curbed. Politically, using the central bank to print money is the easiest choice. Until the deflationary effects of technology are proven, investors should align their strategies with the times.

New York—Correspondent Bin Nansa binthere@hankyung.com

Korea Economic Daily

hankyung@bloomingbit.ioThe Korea Economic Daily Global is a digital media where latest news on Korean companies, industries, and financial markets.

!['Easy money is over' as Trump pick triggers turmoil…Bitcoin tumbles too [Bin Nansa’s Wall Street, No Gaps]](https://media.bloomingbit.io/PROD/news/c5552397-3200-4794-a27b-2fabde64d4e2.webp?w=250)

![[Market] Bitcoin falls below $82,000...$320 million liquidated over the past hour](https://media.bloomingbit.io/PROD/news/93660260-0bc7-402a-bf2a-b4a42b9388aa.webp?w=250)