Editor's PiCK

Is the end of China-originated 'ultra-low-price era'?…Will a global price shock occur? [Global Money X-file]

Summary

- China's anti-neijuan policy and strong supply reforms have eased the oversupply of low-priced goods, which could raise global inflationary pressure.

- These changes could affect import prices and the pace of rate cuts in major economies such as the U.S. and Europe.

- For Korea, steel and petrochemicals may gain while battery materials may face higher costs, producing a dual impact.

Recent analysis suggests China-originated deflationary exports have peaked. This is because the Chinese government is curbing wasteful excessive competition among domestic companies. Some analysts say that if oversupplied low-priced Chinese goods decline, it could stimulate global inflation. China’s deflationary exports have been one of the factors suppressing global inflation in recent years.

China export price index rebounds

On the 29th, Reuters reported that China's National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) said last month China's Producer Price Index (PPI) fell by 2.1% year-on-year. It continued a 37-month streak of negative readings, a figure showing deflationary pressure within China.

However, the decline narrowed compared with September (-2.3%). In particular, the downward trend in prices of key industrial goods such as solar panels and steel, which are the focus of Chinese government policy, has noticeably slowed. At the same time, analyses say Chinese companies' pain has reached its limits. Last month, industrial profits in China fell by 5.5% year-on-year. This marked a sharp reversal from the increases seen in the previous two months.

China's export price index has rebounded. After declining since 2022, it rose by 0.5% year-on-year in June. This was the first positive turn in 25 months. Last month, China's merchandise export prices (in dollar terms) also rose by about 1.5% month-on-month. This is why some analysts say China-originated deflationary exports may have passed their peak. However, as of August, China's export prices remained about 17% below the 2022 average.

Recently, the Chinese government has tightened the reins on what it calls a strong 'anti-neijuan' policy. China's leadership has expressed a strong will not to tolerate 'malignant infinite competition' that hinders the qualitative growth of the economy, i.e., neijuan (内卷·Neijuan). The term 'neijuan' was originally used by anthropologist Clifford Geertz to describe a phenomenon in agricultural societies where inputs rise without corresponding output growth.

But in 2020s Chinese society, the word came to refer to a 'zero-sum game' where companies pursue price-cutting competition without technological innovation and mutually destroy each other. The third-term leadership of Xi Jinping has defined 'neijuan' as a bad custom that must be eradicated because it blocks the qualitative growth of the Chinese economy.

Analysts say this stems from a structural sense of crisis facing the Chinese economy. China’s growth has slowed due to a combination of long-term weakness in the real estate market and massive debt. The Chinese economy has suffered from chronic oversupply. The problem was particularly severe in industries that received strategic government support. Solar, batteries, and electric vehicles grew explosively on the back of massive government subsidies and cheap finance, but this led to uncontrollable oversupply.

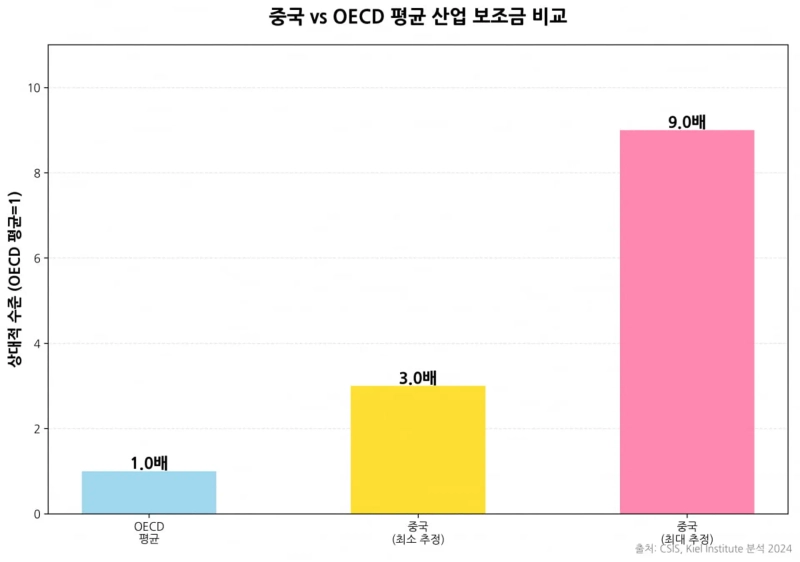

According to an analysis cited by the U.S. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) from the Kiel Institute, China’s industrial subsidies are 3–9 times the OECD average. Such abnormal support has accumulated structural excess capacity, the report says. Reuters' analysis in August found that Chinese solar panel manufacturers have production capacity roughly twice global annual demand.

With weak domestic demand, companies were driven into cutthroat competition to survive. Bloomberg analysis estimates that 34% of Chinese companies are in a 'zombie firm' state this year, unable to cover even interest costs— the highest in 25 years. There is also analysis that about 25% of China's listed companies recorded operating losses in the first half of this year.

This domestic slump in China spilled outward. Chinese firms pushed inventories overseas to offset weak domestic demand, leading to price collapses in global markets. According to U.K. economic research firm Capital Economics, China’s export prices fell by about 17–20% since mid-2022.

Chinese low-priced goods that kept global inflation down

This acted as a disinflationary factor that pulled down importers' prices. At the same time it threatened the manufacturing base of importing countries and intensified global trade frictions. Jörg Wuttke, former president of the European Chamber of Commerce in China, lamented in an interview with EuroBiz that "China's overproduction was an existential threat to European companies." Brad Setser, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, pointed out that "China's manufacturing goods surplus (exports minus imports) exceeds $2 trillion, which is about 10.5% of China’s GDP."

China's leadership judged this could not be left unchecked. In a September contribution to the Communist Party theoretical journal Qiushi, President Xi Jinping said, "We must accelerate the orderly removal of outdated and inefficient production capacity and improve the quality and efficiency of development," and emphasized "". At the Politburo meeting in July, it set as core tasks for the second half of the year "strengthening the management of disorderly competition" and "strengthening the clearance of duplicated and excess production capacity in some industries."

This is being seen as a 'second supply-side reform' that differs in trajectory from past supply-side reforms. The first reform in 2015 focused on physically closing steel and coal facilities centered on state-owned enterprises. The current anti-neijuan policy is viewed as a highly sophisticated market intervention strategy that halts the private sector's chicken game and induces an orderly market reorganization.

George Magnus of the Oxford China Centre wrote in a recent Financial Times contribution that "Xi's anti-neijuan drive is an expression of economic desperation," and diagnosed that "they know that if they cannot resolve overproduction, the Chinese economy cannot avoid 'becoming Japanified.'"

China's anti-neijuan policy is not just a slogan. Analysts say it has been concretized into a multi-layered policy package covering finance, environmental standards, judicial liquidation procedures, and supply chain trading practices. It is a powerful braking mechanism that exhausts the very ‘‘stamina’’ of companies that could sustain indiscriminate price-cutting competition.

Among the anti-neijuan measures this year, the most disruptive is considered the forced change in supply chain finance structures. In March, the State Council revised the 'Regulations on Payment Guarantees for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises' and fully implemented them from June. The core obligation is that 'large and state-owned enterprises must pay for goods or services received from small suppliers within 60 days.' Penalties for violations have been significantly strengthened. Contract terms that require subcontractors to wait until the final customer pays before receiving payment are also prohibited.

This is evaluated as a move that shakes the foundation of China’s industrial structure. Until now, big Chinese companies in electric vehicles, batteries, and solar often used long bill payment cycles or payment delays of six to twelve months. They effectively used subcontractors' funds as 'interest-free working capital.'

This acted as a 'hidden subsidy' allowing large firms, on the basis of abundant cash liquidity, to sustain long-term cutthroat competition that put competitors out of business. Small and medium-sized suppliers had no choice but to accept deliveries below cost to meet large firms' demands. Critics say this contributed to price decline pressures across entire industries.

Indeed, with the payment cycle being forced to 60 days, large firms have faced increased cash-flow pressure. No longer able to appropriate subcontractors' funds, their financial capacity to sustain aggressive production expansion and low-price bidding has shrunk—what some call a 'financial brake.' About 20 major automakers, including BYD, Great Wall Motor (GWM), and Xiaomi Auto, announced immediately after the June implementation that they would comply with the 60-day payment cycle.

'Technical standards' and 'energy quotas' are also seen as promoting a sophisticated market exit. Beyond simply reducing production volumes, this is a structural approach to permanently remove inefficient facilities from the market. In September, the Standardization Administration of China (SAC) and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) announced a draft mandatory standard that significantly tightens per-unit energy consumption limits for polysilicon production.

Industry analysis says that if this standard is strictly applied, about 20–30% of domestic polysilicon production capacity—older facilities—could be forced out. It is one of the most certain means to physically resolve oversupply.

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) has also stepped in. For the 2025–2026 renewable energy consumption quota system, it specified, for the first time, concrete renewable energy usage ratios for sectors including steel, cement, polysilicon, and data centers. The end-of-August order to cut output by roughly 30% at steel mills in Tangshan, Hebei Province, is interpreted in this context.

The exit of 'zombie firms' has long been a task for the Chinese economy. Under the anti-neijuan campaign, the intensity of implementation has changed. The State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) and financial authorities have cut off credit supply to companies that survive only on government subsidies and policy bank loans without generating profits.

This second half, major commercial banks in China have significantly tightened loan review standards for marginal firms. There are increasing reports of refusals to extend maturities. Pan Gongsheng, governor of the People's Bank of China, emphasized in a keynote at a financial forum in September that "indiscriminate funding support for zombie enterprises subject to restructuring will be blocked."

The draft amendment to the Price Law announced in July also explicitly aims to regulate neijuan-style low-price competition and restore market order. Anti-neijuan policies have not been applied uniformly across all industries. The main targets are sectors with the most severe supply overhang: solar, steel, batteries, and electric vehicles.

Industry participants say China's deflationary exports have not completely disappeared. They are at a stage where the intensity of price destruction has peaked and is receding. Chinese firms can no longer dump goods below cost due to constraints such as the 60-day payment rule and energy quotas. This raises the floor of global tradable goods prices. Deflationary pressure will gradually weaken.

Could this spur global inflation?

China’s anti-neijuan policy could be a factor that raises inflationary pressure globally. Advanced economy central banks have said that low-priced imports from China contributed to lowering inflation. If this effect disappears, the global inflation trajectory could be revised upward.

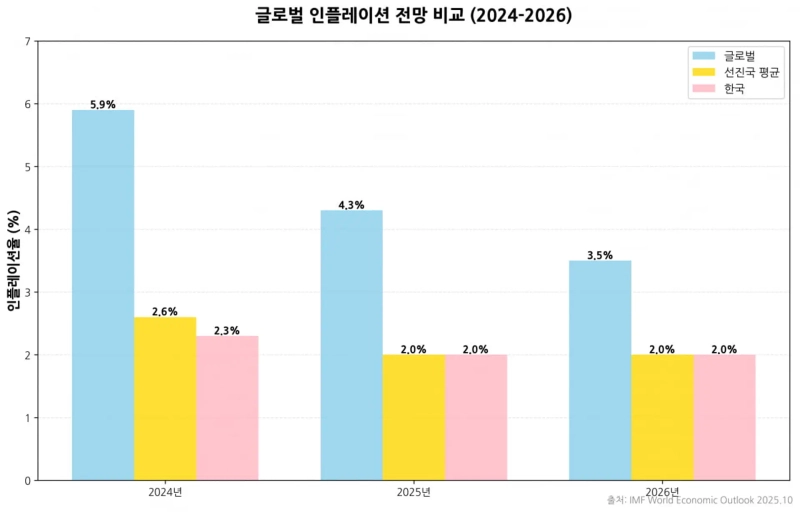

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects global inflation to stabilize around 3.5% next year. But if China’s supply reforms operate strongly, goods inflation could remain higher than expected. Price increases in Chinese products could push up import prices in the U.S. and Europe, potentially sustaining already-high service prices and creating 'sticky inflation.'

Macquarie’s Larry Hu, chief China economist, recently told Bloomberg that "anti-neijuan ultimately aims to restore firms' 'price-setting power,'" and analyzed that "this could raise the floor of China-originated export prices and weaken the global disinflationary effect."

This could slow the pace of interest-rate cuts by the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) and the European Central Bank (ECB). If the era of cheap Chinese goods ends, rising global supply-chain costs could structurally lift the neutral rate (the rate that neither overheats nor cools the economy). That would mean central banks may need to keep interest rates higher for longer to achieve inflation targets.

In the U.S., price rises for Chinese imports could compound inflationary pressure together with the Trump administration’s tariff policies. This would complicate the Fed’s policy operations further, making it more hesitant to cut rates amid recession concerns.

South Korea is sensitive to changes in China’s supply-chain policies. Korea’s export share to China exceeds 20%. China’s anti-neijuan policy will have two simultaneous effects on Korea’s key industries: 'positive spillovers' and 'cost increases.' If China’s excess capacity is controlled, the biggest beneficiaries will be steel and petrochemicals, industries that have long suffered profitability deterioration due to China’s low-price offensive.

If cutthroat competition in batteries and solar eases, Korean firms could be favored in defending global market share based on technology and quality. Display and general machinery sectors could also see lower cutthroat competitive pressure as neijuan competition within China eases.

On the other hand, there are risk factors. Industries that heavily rely on Chinese raw materials and intermediate goods—such as battery materials, rare earths, and commodity chemicals—could face cost increases. Overlapping Chinese environmental regulations and export controls could worsen supply-chain instability.

[Global Money X-file traces important but little-known global flows of money. To conveniently receive necessary global economy news, please subscribe to the reporter page]

Reporter Kim Joo-wan kjwan@hankyung.com

Korea Economic Daily

hankyung@bloomingbit.ioThe Korea Economic Daily Global is a digital media where latest news on Korean companies, industries, and financial markets.![[Market] Bitcoin slips below $77,000…Ethereum also breaks below $2,300](https://media.bloomingbit.io/PROD/news/f368fdee-cfea-4682-a5a1-926caa66b807.webp?w=250)

!['Easy money is over' as Trump pick triggers turmoil…Bitcoin tumbles too [Bin Nansa’s Wall Street, No Gaps]](https://media.bloomingbit.io/PROD/news/c5552397-3200-4794-a27b-2fabde64d4e2.webp?w=250)