"No missiles or semiconductors without China"… US 'choked by rare earths' [Global Money X-file]

Summary

- China is strengthening control over the entire rare earth supply chain and related technologies, raising the likelihood of severe supply chain risks for Western advanced industries and defense sectors.

- It said this will directly constrain Western supply chain diversification strategies regarding rare-earth permanent magnets, essential materials for key industries such as electric vehicles, wind power, and semiconductors.

- The U.S. and Europe are pursuing policies to build domestic rare earth supply chains, but analysts say short-term crisis resolution is difficult due to practical limits such as the lack of mid-rare earth separation facilities.

!["No missiles or semiconductors without China"… US 'choked by rare earths' [Global Money X-file]](https://media.bloomingbit.io/PROD/news/e04fd451-8c7f-4c6c-a920-5c4740635876.webp?w=800)

China is tightening control over the rare earths supply chain. Beyond simple raw material export restrictions, it is moving to 'full value-chain control' by seizing core technologies, equipment, and intellectual property needed to produce high-performance permanent magnets that serve as the 'heart' of advanced industries. Analysts view this as retaliation against U.S. semiconductor technology restrictions.

Shaking the global supply chain with rare earths

According to Reuters on the 13th, China's Ministry of Commerce on the 9th announced the "export control decision on overseas (offshore) rare earth materials." It included samarium, dysprosium, gadolinium, terbium, lutetium, scandium, yttrium metals and samarium-cobalt alloys, terbium-iron alloys, dysprosium-iron alloys, terbium-dysprosium-iron alloys, dysprosium oxide, and terbium oxide as export-controlled items.

These materials require an export license for dual-use goods (goods that can be used for both military and civilian purposes) issued by China's Ministry of Commerce when exported. It also placed overseas-manufactured rare-earth permanent magnet materials and rare-earth target materials that contain, combine, or mix these materials under export control. The export controls on these items will be implemented in stages starting from the 8th of next month.

The key of this measure is that it expands to all related technologies and core equipment used in mining, concentration, smelting, separation, alloying, and magnet manufacturing. Specifically, it added five rare earth elements—holmium (Ho), erbium (Er), thulium (Tm), europium (Eu), ytterbium (Yb)—to the control list, expanding the controlled elements to a total of 12.

This is assessed to be stronger than the quantity-control approach used in 2010 during the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu Islands in Chinese) dispute with Japan, when export quota reductions were used. While that measure caused temporary price spikes and supply shocks, analysts say this new measure has a long-term objective to fundamentally hinder and delay Western efforts to build independent rare earth supply chains.

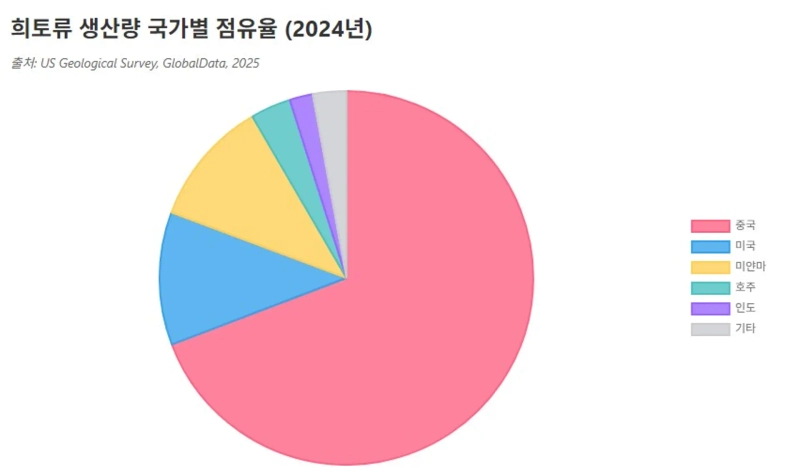

China's dominance of rare earths is overwhelming. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), China accounts for about 70% of global rare earth mining this year. At the bottleneck refining/separation (oxide production) stage it controls about 90%, and in final product permanent magnet manufacturing it controls about 93%.

Rare earth refining and separation processes require advanced chemical technology and know-how. They also cause severe environmental pollution. Over past decades, Western countries moved these processes to China for cost efficiency and environmental regulation reasons. Now, based on accumulated technical advantages, China has shown intention to exert control not only over the physical supply chain but also over the 'knowledge bottleneck'—exerting dominance over the entire value chain.

Dr. Gracelyn Baskaran of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) said, "Beijing is no longer content to be an indispensable raw material supplier to the world," adding, "Now they want to be the gatekeeper of the technologies needed to use those raw materials." She emphasized, "This fundamentally changes the rules of the game."

Using rules similar to the U.S. 'Foreign Direct Product Rule'

The most powerful and controversial aspect of this control measure is that it adopts a logic similar to the U.S. 'Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR)' used to control the semiconductor supply chain. China's new regulation makes products that contain even trace amounts of Chinese rare earths (for certain mid-rare earths, a threshold of 0.1% of product value) or products manufactured overseas using Chinese technology and equipment subject to export licensing.

Analysts say this is intended to nullify Western firms' attempts to bypass China by building processing facilities in third countries like Vietnam or Malaysia. For example, if a U.S. company imports neodymium oxide from China and processes it into magnets in a Vietnamese factory, the product would fall under China's control if Chinese-made equipment or alloying technologies were used in that process. This directly targets the so-called 'China-plus-one (+1)' strategy, a key supply chain diversification tactic.

Applying such 'extraterritorial jurisdiction' imposes huge regulatory burdens on Western firms. It also provides an unprecedented opportunity for the Chinese government to gather information. To obtain export licenses, companies must submit sensitive supply chain information to Chinese authorities, such as end users, detailed product specifications, and how technologies are applied. This could take on the character of an intelligence operation accumulating deep information about Western advanced industry ecosystems beyond trade control. Critics say it is akin to building a massive 'panopticon' monitoring the entire global rare earth value chain.

A White House official told Reuters on the 9th, "The White House and relevant agencies are closely assessing the impact of China's newly announced rules as China attempts to control global technology supply chains without notice."

U.S. President Donald Trump said on the 10th, "China has sent a letter saying it will control global rare earth exports," and added, "One of the measures under review is significantly raising tariffs on products the U.S. imports from China." The U.S. decided to impose an additional 100% tariff on China starting from the 1st of next month in response to China's rare earth export controls.

Analysts say China's new rules mainly target defense and semiconductor companies. License applications that could be used for military purposes are, in principle, denied, and semiconductor-related applications are to undergo very strict case-by-case reviews. Observers say China has begun to use rare earth dominance as a geopolitical weapon to weaken Western military technological superiority and advanced industry competitiveness.

George Chen, a partner at the Asia Group, said, "This isn't a blunt instrument like a total ban; it's more like a scalpel," adding, "China can raise or lower pressure on specific companies, industries, or countries to achieve precise political objectives." Analysts compare China's rare earth controls to a sophisticated 'surgical scalpel.'

The dilemma of advanced defense and green agendas

China's rare earth control strategy strikes precisely at two goals pursued by the U.S. and others at the same time: 'strengthening national security' and 'green energy transition.' Both stem from vulnerabilities in the same supply chain. The core components of cutting-edge weapon systems and the drivers of a green economy both rely on rare-earth permanent magnets controlled by China, particularly the neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) family of magnets.

The performance of modern weapon systems depends on high-efficiency, high-power, small, lightweight components. According to the U.S. Congressional Research Service (CRS), an F-35 stealth fighter is reported to use about 418 kg of rare earths. An Arleigh Burke-class Aegis destroyer uses about 2,360 kg, and a Virginia-class nuclear submarine uses about 4,170 kg of rare earths.

These magnets are essential in all parts that serve as the brain, heart, and muscles of weapon systems: aircraft electric actuators, microwave energy focusing devices in advanced AESA radars, guidance systems of JDAMs and Tomahawk missiles, and propulsion motors of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs).

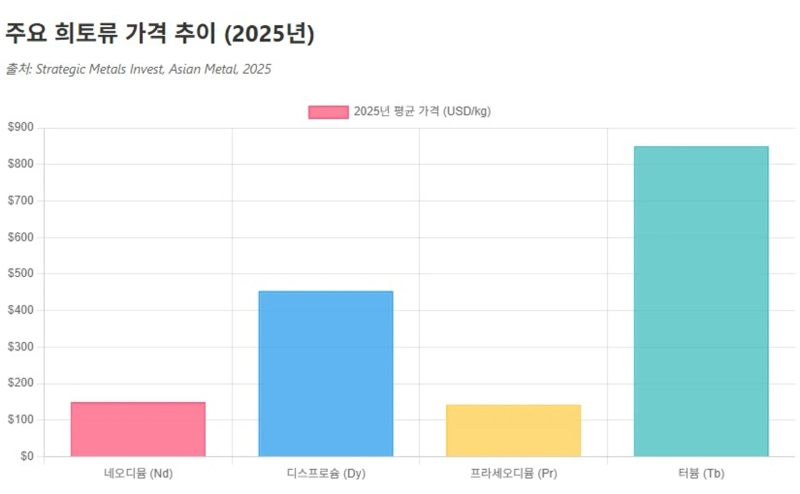

According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), as of last year the defense sector's demand accounted for less than 0.1% of the total rare earth market, a negligible share. The issue is not total volume but reliably sourcing the highest-grade magnets that must withstand extreme temperatures and pressures. For high-temperature performance, mid-rare earths (HREEs) such as dysprosium (Dy) and terbium (Tb) must be added. China virtually controls the separation market for these mid-rare earths at nearly 100%. China's control could pose a direct threat to the West's ability to maintain military capabilities.

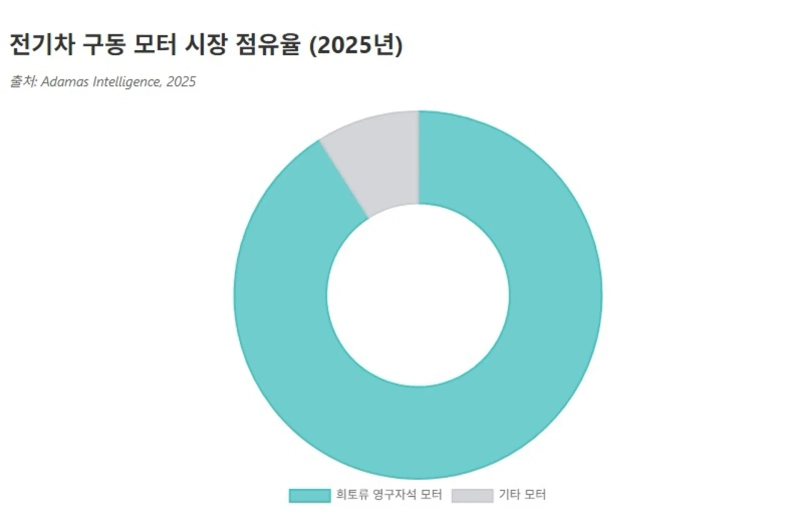

The green energy transition has also increased dependence on rare earths. Data from market research firm Adamas Intelligence shows that this year rare-earth permanent magnet (PM) motors account for about 91% of the global electric vehicle drive motor market by power contribution. This means nearly all electric vehicles on the road currently depend on Chinese rare-earth magnets.

Offshore wind power is similar. The direct-drive method, which connects the generator directly without a gearbox to rotate large blades at low speeds, has become common. These permanent magnet generators (PMGs) require several tons of neodymium (Nd), praseodymium (Pr), dysprosium (Dy), and terbium (Tb) per turbine. A single 15MW-class ultra-large offshore wind turbine needs about 3–4 tons of NdFeB magnets. According to a U.S. Department of Energy report, about 76% of offshore wind turbines adopted this PMG method.

The more climate policies such as the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and Europe's Green Deal promote electric vehicles and wind power deployment, the more demand will grow for rare-earth magnets controlled by China. The aim of addressing the climate crisis paradoxically strengthens the economic power of a geopolitical competitor while deepening one's own strategic vulnerabilities.

The semiconductor industry's dependence on rare earths is also critical. High-strength NdFeB magnets are essential for precise control in semiconductor manufacturing equipment. Core driving components of advanced semiconductor equipment—robot arms transporting wafers, precision motors inside deposition and etching process chambers—mostly use rare-earth magnets.

Rare earths are also needed in chemical mechanical planarization (CMP) processes. For sub-7-nanometer processes, flattening the wafer surface at the atomic level is crucial. The key ingredient in the slurry used for this polishing is cerium oxide (ceria), an oxide of the rare earth element cerium. This is why China recently specified semiconductor manufacturers in its export control targets. It is known that, with current technology, it is difficult to find alternatives to ceria slurry for CMP processes.

Jacob Feldgoise, a senior analyst at Georgetown University's Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET), said, "When people think of chips they think of silicon, not the yellow powder (ceria)," adding, "But without that ceria slurry you can't make chips, and although the quantities are small, the dependence has large ripple effects."

Limits of U.S. and European alternatives

In response to China's strengthened rare earth controls, the U.S. and Europe are pursuing policies to rebuild domestically centered supply chains. The core of the U.S. response is the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), which will ban the use of Chinese rare-earth magnets in defense systems starting in 2027. This ban is a very powerful regulation covering the entire supply chain from mining to final magnet production. Since 2020, the U.S. Department of Defense has invested more than $439 million to support domestic supply chain construction.

The U.S. government plans to secure an annual magnet production capacity of 10,000 tons by 2028 through a multi-billion-dollar partnership with MP Materials. The U.S. Defense Logistics Agency has launched about $1 billion in global procurement to stockpile critical minerals. The Department of Defense has also engaged in strategic equity investments, such as acquiring a 10% stake in Trilogy Metals linked to the Ambler project in Alaska.

Despite the U.S.'s strong industrial rebuilding will, analysts say there are significant practical obstacles. MP Materials has begun oxide production in the U.S. and is building its first magnet plant, showing concrete progress. However, the U.S. lacks separation and refining facilities for essential mid-rare earths (HREEs), particularly dysprosium (Dy) and terbium (Tb), which are critical for high-performance magnet manufacturing.

The European Union (EU) is responding with the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA). The CRMA sets targets to source 10% of the EU's annual consumption from domestic mining, 40% from domestic processing, and 25% from domestic recycling by 2030, and aims to reduce dependence on third countries for certain strategic raw materials to below 65%. To achieve this, it designates 'strategic projects' and simplifies permitting procedures and improves financial access through incentives.

There are many obstacles here as well. Economically viable rare earth mines are scarce in Europe. New mining projects often face local opposition for environmental reasons. Re-shoring the pollution-prone refining and separation facilities that were once moved to China is politically sensitive and difficult.

Korea's high dependence on overseas rare earths

Korea's dependence on overseas critical minerals exceeds 99%. It effectively relies entirely on imports. For rare earths, imports from China exceed 70%. Dependence on finished permanent magnets is even more serious. With the growth of the electric vehicle market, imports of permanent magnets nearly tripled from $239 million in 2020 to $641 million in 2022. Most were imported from China. In April, China announced export control measures and even directly warned Korean companies not to supply parts containing Chinese rare earths to U.S. defense contractors.

[Global Money X-file examines important but little-known flows of global money. Subscribe to the reporter page to receive necessary global economic news conveniently.]

Reporter Kim Joo-wan kjwan@hankyung.com

Uk Jin

wook9629@bloomingbit.ioH3LLO, World! I am Uk Jin.

!['Easy money is over' as Trump pick triggers turmoil…Bitcoin tumbles too [Bin Nansa’s Wall Street, No Gaps]](https://media.bloomingbit.io/PROD/news/c5552397-3200-4794-a27b-2fabde64d4e2.webp?w=250)

![[Market] Bitcoin falls below $82,000...$320 million liquidated over the past hour](https://media.bloomingbit.io/PROD/news/93660260-0bc7-402a-bf2a-b4a42b9388aa.webp?w=250)